Introduction

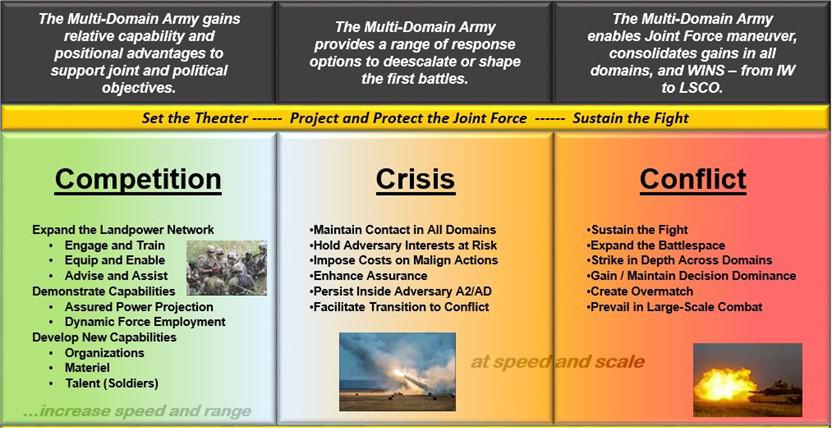

The United States is facing an unprecedented set of challenges to our national interests. In the coming years, threat nations will have weaponized all instruments of national power (economic, diplomatic, informational, and military) to undermine the ability of the United States, its allies, and partners to project power to protect their vital interests during all phases of the conflict continuum (competition, crisis, armed conflict, and return to competition), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conflict Continuum (Source: U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command [TRADOC] [1]).

Threat capabilities will lead to an unstructured international environment where the lines between conflict and peace are blurred. Threat nations will leverage technological advances that have enabled the integration of space, cyber, information, and electronic warfare (EW) capabilities to shape the conflict continuum environment to attempt to thwart American power projection capabilities during transition from competition to armed conflict.

There is an urgent need for transformational change in how the United States exercises its national power capabilities and counters those of threat nations to meet these emerging challenges, particularly how they support the military instrument of national power during transition to armed conflict. The protection of critical infrastructure (CI) is now and will become even more important to ensure projection of military power capabilities.

CI

Protection of CI is an essential function of the Department of Homeland Security. CI includes “assets, systems, and networks, whether physical or virtual, that are considered so vital to the United States that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination thereof” [2]. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) indicates that there are 16 CI sectors, identified as the following [2]:

- Agriculture and Food

- Chemical and Hazardous Materials Industry

- Defense Industrial Base

- Government Facilities

- Nuclear Reactors, Materials, and Waste

- Communications

- Financial

- Critical Manufacturing

- Emergency Services

- Information Technology

- Transportation

- Commercial Facilities

- Dams

- Energy

- Healthcare and Public Health

- Water and Water Treatment Systems

Protection of CI has become increasingly relevant for the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) in its ability to project power across the competition continuum, including competition, crisis, conflict, and return to competition, as the homeland is no longer viewed as a sanctuary [3].

Multidomain Operations (MDOs)

Historically, the United States has engaged in military conflict outside the continental United States. In the past, the advantage of geography has provided a sanctuary from which the country has had the ability to project power from with little opposition. Because of emerging threat capabilities, the U.S. military can no longer view the continental United States as a sanctuary because the likelihood of a threat nation, as well as nonstate actors, disrupting and/or delaying our power projection capabilities through direct and asymmetric means is becoming more assured. Power projection, as defined by different versions of Joint Publication (JP) 3-35, is “the ability of a nation to apply all or some of its elements of national power – political, economic, informational, or military – to rapidly and effectively deploy and sustain forces in and from multiple dispersed locations to respond to crises, to contribute to deterrence, and to enhance regional stability” [4].

In the Joint Operating Environment 2035: “The Joint Force in a Contested and Disordered World,” dated 14 July 2016, it states, “For the foreseeable future, U.S. national interests will face challenges from both persistent disorder and states contesting international norms…” [5]. As the Joint Force responds to adversaries contesting international norms in either competition or armed conflict, it will conduct operations in an emerging operational environment shaped by the following four interrelated characteristics:

- Adversaries are contesting all domains, the electromagnetic spectrum (EMS), and the information environment. U.S. dominance is not assured.

- Smaller armies fight on an expanded battlefield that is increasingly lethal and hyperactive.

- Nation states have more difficulty in imposing their will within a politically, culturally, technologically, and strategically complex environment.

- Near-peer states more readily compete below armed conflict, making deterrence more challenging.

These characteristics allow adversaries, particularly near-peer threats like China and Russia, to expand the battlefield in time (a blurred distinction between peace and war), in domains (space and cyberspace), and in geography (now extended into the homeland) to create tactical, operational, and strategic standoff.

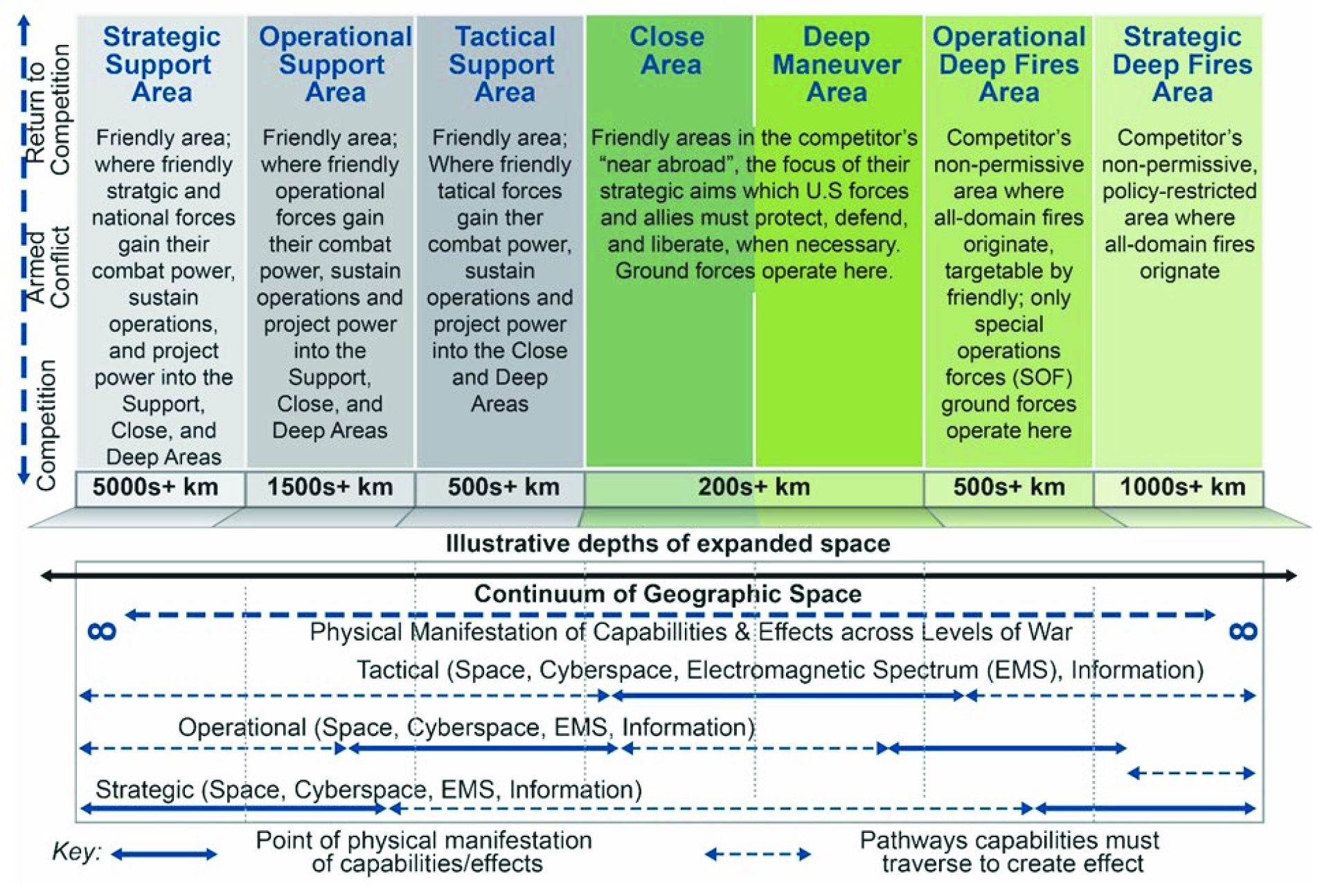

The MDO concept, depicted in Figure 2, considers operations in seven domains (space, cyber, air, land, maritime, information, and EMS) across seven MDO framework spaces (Strategic Support Area [SSA], Operational Support Area, Tactical Support Area, Close Area, Deep Maneuver Area, Operational Deep Fires Area, and Strategic Deep Fires Area). The homeland is part of the SSA. Each of the spaces contributes to the ability of military forces to successfully complete operations.

Figure 2. MDOs Areas and Domains (Source: TRADOC [6]).

Support Areas

Collectively, these areas represent that space in which the Joint Force seeks to retain maximum freedom of action, speed, and agility and counter the enemy’s multidomain efforts to attack friendly forces, infrastructure, and populations. The nature of these threats varies with the adversary; although with current technology, virtually all adversaries will have reached into the homeland (e.g., through cyberspace, information warfare [IW], agents, sympathizers, and space), even if only by using social media to undermine public support and encourage “lone-wolf attacks.” The reach of regional powers is also growing, and the most potent adversaries already possess multiple advanced cyberspace, space, and physical capabilities (air, naval, special operations, and/or missile forces) that can always contest the friendly rear areas. Though enemy capabilities will vary with the situation, a common requirement will be the need to ensure that responsibilities, resources, and authorities are properly aligned among echelons, functions, and political organizations.

Support areas are divided according to friendly and enemy capabilities typically operating in each area.

The SSA

This is the area of cross-combatant command coordination, strategic sea and air lines of communications, and the homeland. Most friendly nuclear, space, and cyberspace capabilities and important network infrastructure are controlled and located here. Joint logistics and sustainment functions required to support MDO campaigning throughout competition and armed conflict emanate from the SSA. The enemy will attack the SSA to disrupt and degrade deployments and reinforcements attempting to gain access to the Operational Support Area and move to the Close Area, taking advantage of the reach of strategic lethal and nonlethal weapons, as well as special operations reconnaissance and strikes. Enemy engagements in this area will drive a rapid tempo of friendly operations in other areas to seek decision and limit enemy options for escalation.

The Operational Support Area

This is the area where many key Joint Force mission command, sustainment, and fire/strike capabilities are located; these can be land or sea based. This area normally encompasses many entire nations, thus making it an important space for friendly political-military integration. Due to the political and military importance here, the enemy targets this area with substantial reconnaissance, IW, and operational fires capabilities.

The Tactical Support Area

This area directly enables operations in the Close, Deep Maneuver, and Deep Fires Areas. Many friendly sustainment, fires, maneuver support, and mission command capabilities are here. The enemy directs IW, unconventional warfare, tactical fires, maneuver forces, and even operational fires at friendly forces, populations, and civil authorities.

Operational and Strategic Deep Fires Areas

These areas are defined as those beyond the feasible range of movement for conventional forces but where Joint fires, Special Operations Forces, information, and virtual capabilities can be employed.

Deep Maneuver Area

This is the highly contested area where conventional maneuver (ground or maritime) is possible but requires significant support from multidomain capabilities; commanders must make a concerted effort to “break into” this area. Because more friendly capabilities possess the range and survivability to influence or operate within this space than in the Deep Fires Area and commanders can take advantage of fire and movement, there are many more options for Joint Force employment here than in the Deep Fires Area.

Close Area

This area is where friendly and enemy formations, forces, and systems are in imminent physical contact and will contest for control of physical space in support of campaign objectives. This area includes land, maritime littorals, and airspace.

Protection of CI

Direct adversarial action against homeland infrastructures, assets, and personnel in the SSA poses the greatest risk to power projection capabilities. The TRADOC assessment of the future operational environment identifies eight homeland sectors particularly vulnerable to such disruption [1]:

- Agriculture and food supply – Those areas affecting acquisition, processing, and availability of foodstuff.

- Finance, banking, and commerce – Disruption of financial networks, availability of funds, confidence in markets, and access to retail.

- Rule of law/government institutions – Degrade confidence in the government’s ability to provide functioning, stable, and legitimate law and order, services, and governance.

- Transportation – Prolonged interruption of air, cargo, and public sectors.

- Medical – Loss of services, corruption of supply chain, and inability to react to pandemics.

- Water – Contamination of public supply, disruption of distribution, and loss of access to water.

- Power – Disruption to the electromagnetic spectrum over wide areas and interdiction of power generation.

- Entertainment and information – Attacks against arenas and public gathering places, prolonged internet denial, and loss of confidence in journalism.

By targeting CI in the homeland, adversaries will attempt to delay U.S. forces’ capacity to respond to events, tying up critical military homeland assets with Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) responsibilities and eroding the nation’s support for military operations. In addition, adversaries may also time their CI attacks to take advantage of an ongoing natural disaster or DSCA activity in the homeland to amplify their effects.

CI supporting deployment activities critical to power projection capabilities and installation/command deployment plans that would likely be targeted for disruption include the following eight sectors:

- Power

- Ports

- Rail

- Road networks

- Airports

- Fuel

- Water

- Communication networks

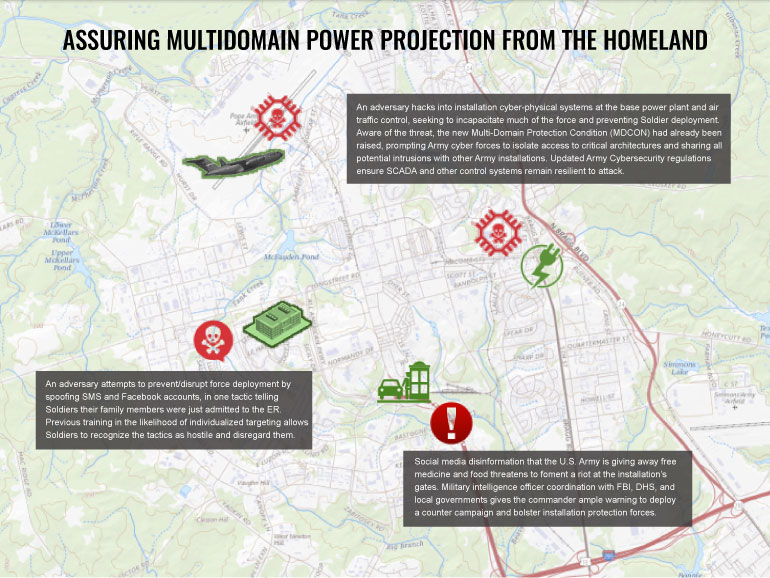

Attacks on the homeland and installation/command deployment plans, which rely heavily on these eight CI sectors, are likely to come from multidomain formations that seek to disrupt power projection capabilities from the other side of the globe. Where possible, adversaries will use multidomain effects to encourage or compel attacks by irregular or asymmetric domestic groups (e.g., narco-terrorists). Adversaries are likely to conduct multiple attacks simultaneously across all domains. Threat courses of action (COAs) will also include the application of new and emerging technologies, especially innovative artificial intelligence/machine-learning (AI/ML) tools.

Threat action categories considered most likely to target CI include the following:

- Cyber-based Effects – Attacks on the homeland will target industrial control systems and supervisory control and data acquisition architectures to degrade or disable systems that control power and water utilities, industrial processes, transportation infrastructures, and other critical networks (e.g., communications). Attacks will also use traditional denial of service and ransomware cyber-based tools.

- IW – Adversaries will deploy online spam, disinformation, and media manipulation tactics to influence public perception and citizen actions, including via social media (e.g., Facebook and Twitter). IW efforts will also seek to translate online sentiments into real-world protests or other hostile demonstrations.

- Unmanned aerial systems (UASs) – Attacks on the homeland will exploit the proliferation of low-cost and expendable UASs (including drone swarms and other autonomous, robotic systems) to deliver payloads to degrade or destroy physical targets; conduct intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions; disseminate powders or other chemical/biological payloads above populations; and directly disrupt airport operations.

- Sabotage – Adversaries will combine information warfare, cyber-based effects, and other means to encourage or compel irregular forces—including suicide bombers, lone-wolf actors, narco-terrorists, and preplaced special forces—to sabotage assets central to the nation’s defense-critical infrastructure (e.g., major highways, utility stations, rail depots, and internet nodes).

- Unconventional attacks – Adversary COAs may use chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear in a manner outside the confines of traditional warfare, namely the targeting of noncombatant populations. Adversaries may also employ electromagnetic pulse weapons, seek to disable the Global Positioning System and conduct widespread jamming of the cellular system and other networks, and exploit as-of-yet unknown vulnerabilities in Smart City/Internet of Things technologies.

The nature of these threats varies with the adversary; although with current technology, virtually all adversaries could reach into the homeland (e.g., through cyberspace, IW, saboteurs, sympathizers, and space), even if only by using social media to undermine public support and encourage “lone-wolf attacks.” The reach of regional powers is also growing, and the most potent adversaries already possess multiple advanced cyberspace, space, and physical capabilities (air, naval, special operations, and/or missile forces) that can always contest the friendly rear areas. Figure 3 provides a visual representation of an attack on the homeland during military deployment.

Figure 3. Example Threat Attack on Deployment (Source: J. Hewett).

For instance, Russia and its proxies have excelled in using cyberattacks to gather intelligence on U.S. military and commercial assets and spread misinformation, while the Chinese People’s Liberation Army has reoriented much of its force to focus on space, cyberspace, and EW operations. Many of these capabilities can originate from anywhere on the globe and project directly into the homeland, threatening to erode Army freedom of action.

Military Installation Reliance on CI

DoD Directive (DoDD) 3020.40, Mission Assurance [7], and DoD Instruction (DoDI) 3020.45, Mission Assurance Construct [8], provide risk-based assessment processes to identify, assess, manage, and monitor the risks to strategic missions. These processes identify defense critical infrastructure vulnerabilities in federal, state, and allied/partner nations assets and infrastructure. Areas of consideration are threats and vulnerabilities, including terrorism; cyberthreats; chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosives; emergency management; extreme weather events such as hurricanes; and loss of utilities. Installation mission assurance must consider CI impacts of unconventional, sequential, or multiple threats such as civil unrest, UASs (to include drone swarms), robotic autonomous systems, IW, cyber, or threats to externally provided support like public utilities or commercial services. Installation protection plans must consider the threats posed by cascading system failures that an adversary is likely to effect via multidomain attack, including disabling a critical system via degradation of a supporting network (e.g., disruption of water purification systems due to debilitation of a base microgrid power controller). It is likely that an incomplete situational awareness of installation vulnerabilities will result in the misallocation of protective measures required in the threat environment.

Commercial companies, suppliers, and distributors play a key role in the homeland by providing electrical, water, telecommunications, trucking, food services, and other critical infrastructure and business services essential to installation and force sustainment and support. Threat nations and nonstate actors operating on their behalf will have sophisticated and diverse capabilities designed to prevent the United States from projecting military power from the homeland. Many of these capabilities can originate from anywhere on the globe and project directly into the homeland, threatening to erode our freedom of action. Threat nations and their proxies have excelled in using cyberattacks to gather intelligence on key CI and military assets and spread misinformation. There are several recent examples reported by multiple news organizations where attacks, accidents, and weather impacted the functioning of infrastructure assets, such as the cyber/ransomware attacks on 7 May 2021 to Colonial Pipeline, an American oil pipeline system, which shut down and delayed fuel distribution for several weeks, and another cyberattack on 30 May 2021, which impacted the world’s largest meat processor, JBS Foods, who had to close its nine beef plants in the United States. The February 2021 winter storm in Texas caused a massive electricity generation failure, leading to shortages of food, water, and heat. Even more recent events, such as the notorious Chinese spy balloon and the train derailment in East Palestine, OH, demonstrate aspects of CI vulnerabilities.

Countering Threats to Militarily Significant CI

Countering the ability of threat nations and nonstate actors’ abilities to successfully employ direct and asymmetric attacks to disrupt and delay the deployment of forces from U.S. installations will require rethinking and synchronizing homeland and defense coordination, planning, and action.

Key CI-related considerations to counter contested deployment of forces from installations include the following:

- Enhance the sustainability and resilience of military installations against enemy action and natural disasters. CI that contributes to this capability would include agriculture and food supply, rule of law/government institutions, transportation, medical, water, and power.

- Increase coordination with partners, particularly in the U.S. domestic private and public sectors, to increase capacity and develop redundancy to protect critical homeland commercial and governmental sectors against disruption.

- Ensure that intelligence generation, collection, and analysis are sufficient to provide installations with all-domain coverage of potential threat courses of action, likelihood of targeting, and risk mitigation of expected outcomes.

- Focus policies and guidance for installation protection on multidomain threats and the risks to cyber-physical systems.

- Develop comprehensive and coordinated analytical methodologies to assess vulnerabilities in homeland installations that are central to deployment.

- Advance the use of AI technologies to enhance commander command, control, and convergence of protection effects. As an emerging capability, AI can provide the ability to generate, ingest, process, format, and analyze large volumes of sustainment and protection data produced at a high velocity/variety, contributing extensively to command-and-control efforts.

- Develop capabilities to detect, target, deny, and conduct post-incident intelligence collection on adversary small UASs or other drone types.

- Establish civil-military relations guidance that is robust for directing how military forces should consult and coordinate with local governments and organizations to defend homeland CI before and during contested conditions.

Conclusions

It is no longer business as usual when it comes to power projection during times of competition, crisis, and transition to armed conflict.

The ability of our nation to deploy forces from the homeland in a time of conflict—supported by political, diplomatic, economic, and informational means—in and across all domains, the electromagnetic spectrum, and the information environment to prevail in competition and armed conflict and then return to competition is an existential requirement.

Protection of CI will facilitate our forces to retain maximum freedom of action, speed, and agility to counter the threat’s multidomain efforts to attack friendly forces, infrastructure, and populations, resulting in a timelier end to crises and return to competition.

References

- TRADOC. The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare. PAM 525-92, October 2019.

- CISA. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “Critical Infrastructure Sectors.” https://www.cisa.gov/critical-infrastructure-sectors, accessed 19 March 2024.

- U.S. DoD. “National Defense Strategy,” 2018.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. Deployment and Redeployment Operations. Joint Publication (JP) 3-35, 10 January 2018.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. “The Joint Force in a Contested and Disordered World.” Joint Operating Environment 2035, 14 July 2016.

- TRADOC. The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028. TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1, 6 December 2018.

- U.S. DoD. Mission Assurance. DoDD 3020.40, 29 November 2016.

- U.S. DoD. Mission Assurance Construct. DoDI 3020.45, 14 August 2018.

Biography

Mark O’Brien is a senior survivability analyst at the SURVICE Engineering Company, where he recently led a team of researchers on behalf of the Homeland Defense & Security Information Analysis Center to complete a capabilities-based assessment for the U.S. Army Maneuver Support Center of Excellence concerning the homeland in MDOs. He is a retired U.S. Army Field Artillery and Army Acquisition Corps Officer. Mr. O’Brien is a graduate of the Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, KS, and holds a bachelor’s degree in economics from Eastern Connecticut State University and a master’s degree in information systems management from Oklahoma City University.