Suicide is a significant and growing problem in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suicide is the tenth leading cause of mortality in the U.S., accounting for almost 45,000 deaths in 2016 [1]. Although mental health concerns are often cited as a primary causal factor for suicide, 52.8% of active-duty service members or reservists who died by suicide in 2016 had no known mental health diagnosis [2].

Suicide prevention is a primary area of focus for the Department of Defense (DoD) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Previously, the suicide rate among civilians had been higher than the military rate. It was thought that this was due to several factors, including “a selection bias for healthy recruits, employment, purposefulness, access to healthcare and a strong sense of belonging [3].” However, this protective effect has eroded over the past two decades.

As of the most recent Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER) in 2016, suicide rates of active-duty service members are on par with those for the U.S. general population [4]. Veterans are at an even higher risk of suicide than active-duty service members, Guard members, or Reservists [5]. The veteran suicide rate in 2016 was approximately1.5 times greater than that of the non-veteran general population [5].

Current Solutions

The VA and DoD have allocated significant resources to reduce suicide rates in active-duty and veteran populations. Multidimensional and multidisciplinary approaches to suicide prevention employed by the DoD include mental health awareness training for all military members; mental health treatment referral guidelines; post-suicide intervention programs; life skills training; and increased staffing of mental health providers [6–11].

In addition to bolstering traditional 24/7 call lines such as the VA’s Veterans Crisis Line and increasing access to “Telemental” health services, researchers across the country have turned to emerging technologies to facilitate the prevention of suicide. This research has primarily focused on creating machine learning algorithms to identify predictive risk factors in the electronic health records of patients [12, 13]. Other approaches to detect suicide risk include using natural language processing (NLP) of text, social media, or auditory conversations [14]; passive sensing of mobile phone data [15]; and developing machine learning algorithms to evaluate risk from self-reported data [16, 17].

Intervention strategies that employ technology include the use of mobile health applications to reduce suicide rates [18] and the development of algorithms to identify optimal suicide prevention strategies [19]. The military has adopted a number of these strategies to improve suicide risk detection and prevention. For example, initiatives such as the VA’s REACH VET, education-based mobile apps, and the VA’s “Make the Connection” outreach campaign have all improved access to resources for atrisk individuals. Despite substantial resources devoted to reducing suicide rates in active-duty and veteran populations, suicide rates remain unacceptably high. Though some initiatives have demonstrated efficacy in reducing rates, the critical question remains: why are suicide rates still increasing?

Barriers to Suicide Rate Reduction

Unfortunately, there are substantial barriers to reducing suicide rates in both active-duty and veteran populations. Although a multitude of factors contribute, there are at least four primary challenges that have significantly impeded progress: access to care, stigma, aversion to

help-seeking, and timeliness of interventions.

Access to Care

Data from the VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention indicate that approximately 70% of at-risk veterans who attempt suicide have not visited VA facilities within the year prior to their attempt [20]. Similarly, nearly one quarter of veterans live in remote, rural areas without easy access to support [21]. Practical barriers include geographical location, availability of resources, access to transportation, time constraints, financial limitations, and the general inconvenience of seeking out professional help [22, 23]. These factors may present as non-trivial obstacles that decrease the likelihood of mental health service utilization.

Stigma

One of the most cited barriers to service utilization in the general population is the stigma associated with mental health treatment [22]. People who experience mental and behavioral health symptoms may experience both public stigma and self-stigma [24]. Public stigma consists of negative perceptions held by others about mental health service utilization and about those who experience mental health challenges. This stigma is particularly acute in military populations, due to concerns about leadership, chain of command, and concerns that service utilization will have a negative impact on career advancement or lead to the loss of a security clearance [25, 26].

Self-stigma consists of the individual’s personal beliefs about mental health issues and service utilization. If an individual has internalized negative perceptions of mental health distress and treatment, it may lead to diminished self-esteem and create a barrier to seeking needed services [24, 27–29].

Aversion to Help-Seeking

Data suggest that both active-duty and veteran populations are hesitant to seek help. In a recent DoD Office of People Analytics study of 14,088 active-duty service members, of those who had experienced suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt since joining the military, 43.3% reported that they had not sought help for their concerns [30]. Among non-help-seekers, most (70.2%) never considered talking to someone about their suicidal ideation. Factors associated with non-help-seeking included being an officer; being male; not being able to identify suicide risk factors nor knowing how to take appropriate action to help; and being concerned about the career impact of seeking mental health treatment [30].

This aversion to help-seeking is likely due to a military culture that values self-sacrifice [31]. Individuals are encouraged to deny their natural instinct for self-preservation and instead to place their own well-being second to their mission. Therefore, mental health concerns may be viewed as a sign of weakness and a liability to others.

Timeliness of Intervention

Many technology-based solutions developed to reduce suicide rates in the military implement previously discussed methods to detect suicide risk. These include scanning the electronic health record for factors that predict increased risk [12, 13], using NLP of social media to identify risk [14], or identifying biomarkers of suicidal ideation [32].

Unfortunately, very few of these efforts have been linked with intervention methods that might avert imminent suicidal gestures. Though services such as the Veterans Crisis Line now offer texting options in addition to 24/7 telephone availability, all of these services require a common element: the service member must be willing to ask for help. Although many service members and veterans do use help lines, the data suggest that an overwhelming majority of individuals at greatest risk of harm do not seek aid at the time of their attempt [12].

Suicide Reduction: A New Model

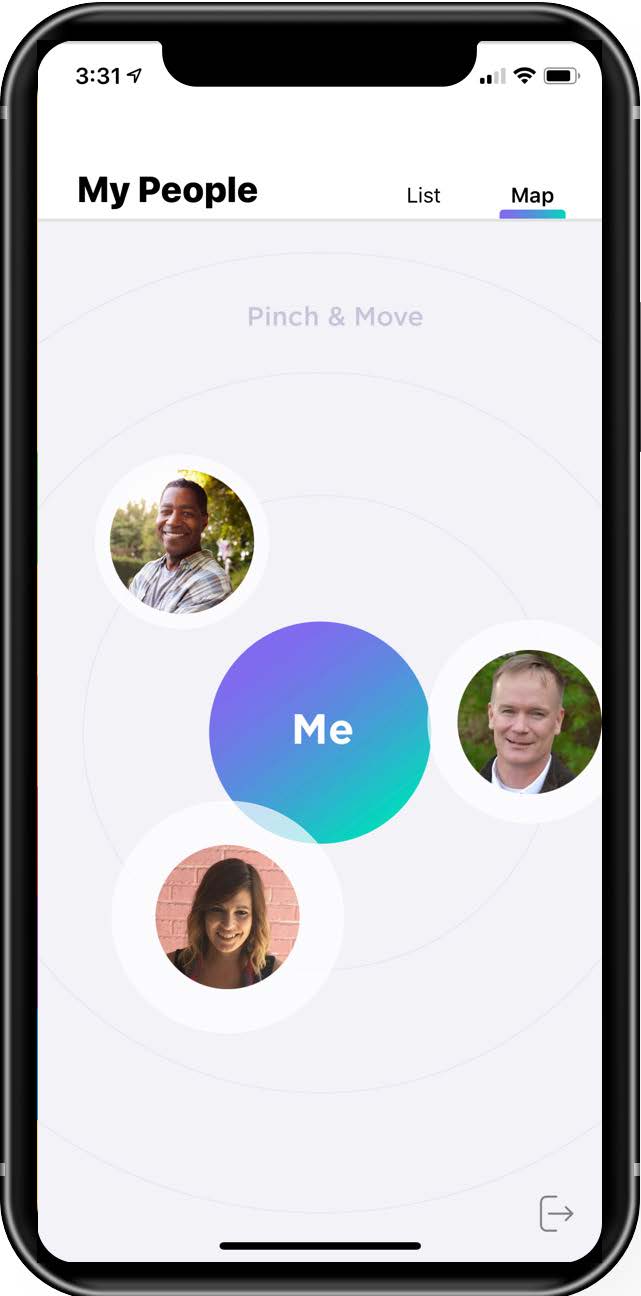

We have developed a novel solution that we call “Voi Reach.” This approach is designed to address all four of the primary barriers to suicide prevention. Our technology provides the user with an easy-to-use mobile app that connects them with a behavioral health coach, and his or her natural support network (e.g., friends, family) to increase safety. We augment this support network with artificial intelligence (AI) and continuous risk monitoring via NLP.

This application provides the first solution capable of predictively identifying an imminent risk of suicide before the user asks for help. This gives DoD medical staff and other first responders the capacity to send an active rescue within moments of an individual needing help. Perhaps most importantly, our technology circumvents major barriers that have previously stymied progress toward the reduction of suicide rates.

Access to care: The app assists veterans and active-duty service members who are not connected with healthcare services. This is particularly helpful for veterans who live in remote areas, and cannot easily access healthcare services because of geographic or physical constraints. Although the app does require the use of an iOS- or Android-capable smartphone, figures from 2014 indicate that up to 79% of all surveyed active-duty Army personnel [33] and up to 90% of veterans [34] own a smartphone. For service members who are capable of using a smartphone and who accept the approach, they are matched with a trained behavioral health coach who provides 24/7 inapp messaging.

The app is built on a patient engagement messaging platform that has serviced over 200,000 patient-provider exchanges to date. Behavioral health coaches are supported by in-app AI algorithms to increase engagement. Our system utilizes proprietary algorithms to prompt the coach on when and how to reach out to the user to maximize engagement. This elevates the quality of care beyond what is currently available through crisis lines, because the coach is more knowledgeable about how to develop and sustain a meaningful relationship with the user.

Stigma/aversion to help-seeking: Though both public and self-stigma will continue to be cultural barriers to accessing care in the military, we believe that our approach has the potential to substantially reduce such stigma: access to care through our app is more private than what is typically afforded through in-person medical or psychotherapy services. Furthermore, with trained veterans serving as behavioral healthcare coaches, military personnel will have more confidence in shared understanding with care providers.

Perhaps most importantly, however, the app provides veterans or active-duty service members the option to invite natural support network members into their care circle. Through a combination of psychoeducation, AI-directed messaging, and direct intervention by behavioral health coaches, this system seamlessly integrates the care of supporting members into the life of an at-risk individual. Our app is consequently a very scalable healthcare solution because a single behavioral health coach can cover hundreds of military personnel.

Timeliness of intervention: Unlike other systems, Voi Reach does not require a veteran to overtly ask for help, as it predicts imminent risk using AI. This solves one of the biggest problems associated with suicide prevention. The app uses advanced NLP to identify at-risk communications within the platform, or through social media (if the user grants permission). This NLP system is built on a specific type of supervised machine-learning system called genetic programming (i.e., a computerized system that can learn to recognize patterns associated with a known outcome) [35].

The system was constructed by converting the free-text records of veterans with known suicide attempts into word or word-phrase datasets, or numerical counts of how often a given word or phrase appeared in a patient record. The derived models then identified the combination of words that were associated with suicide. The data were then analyzed using a machine-learning algorithm to generate predictive models. This approach allows a remote behavioral health coach to be aware instantly when a service member transitions to high risk. Furthermore, a remote coach can then send out emergency services for an active rescue within five minutes of the status change.

Figure 1. Screenshot from the Voi Reach app.

Conclusion

While many technological solutions have been developed to address the problem, suicide rates among active-duty service members and veterans continue to rise. We believe this is due primarily to an inability to stay effectively connected to military personnel and appropriately monitor them for risk long-term. Unlike other solutions, our AI-enabled app-based approach is the first to predict imminent risk, which then allows a behavioral health coach to rapidly reach out to a service member after a risk status change. This is in contrast to other approaches that require those in need of help to ask for it—a problem that, unless we overcome it, will inhibit any significant decline in suicide rates. It is our hope that new, novel applications of technology gain acceptance so that we can move the needle on the tragic and preventable loss of life in the military.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Preven- tion. (2017, March 17). Leading causes of death. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

2. Department of Defense. (2018, June 20). Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER), Calendar Year 2016 Annual Report. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. Retrieved from https://www.dspo.mil/Portals/113/Documents/DoDSER%20CY%202016%20Annual%20Report_For%20Public%20Release.pdf?ver=2018-07-02-104254-717

3. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. (2013, June). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Assessment and Management of Patients at Risk for Suicide (Version 1.0). Assessment and Management of Risk for Suicide Working Group. Retrieved from https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/VADODCP_SuicideRisk_Full.pdf

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, September 29). Preventing suicide. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/fastfact.html?C- DC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fviolenceprevention%2Fsuicide%2Fconsequences.html

5. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2018, September). VA National Suicide Data Report 2005–2016. Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/OMHSP_National_Suicide_Data_Report_2005-2016_508.pdf

6. Bagley, S. C., Munjas, B., & Shekelle, P. (2010). A systematic review of suicide prevention programs for military or veterans. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(3), 257–265. doi:10.1521/suli.2010.40.3.257

7. James, L. C., & Kowalski, T. J. (1996). Suicide prevention in an Army infantry division: A multi-disciplinary program. Military Medicine, 161(2), 97–101. doi:10.1093/milmed/161.2.97

8. Jones, D. E., Kennedy, K. R., Hawkes, C., Hourani, L. A., Long, M. A., & Rob- bins, N. L. (2001). Suicide prevention in the Navy and Marine Corps: Applying the public health model. Navy Medicine, 92(6), 31–36.

9. Knox, K. L., Litts, D. A., Talcott, G. W., Feig, J.C., & Caine, E. D. (2003). Risk of suicide and related adverse out- comes after exposure to a suicide prevention programme in the US Air Force: Cohort study. Bmj, 327(7428), 1376-0. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7428.1376

10. McDaniel, W. W., Rock, M., & Grigg, J. R. (1990, April). Suicide prevention at a United States Navy training command. Military Medicine, 155(4), 173–175.

11. Medical and Dental Care: Members on Duty Other than Active Duty for a Period of More than 30 Days. 10 U.S.C. § 1074a et seq.

12. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2017, April 3). VA REACH VET initiative helps save veterans lives: Program signals when more help is needed for at-risk veterans. News release. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/includes/viewPDF.cfm?id=2878

13. Kessler, R. C., Hwang, I., Hoffmire, C. A., Mccarthy, J. F., Petukhova, M. V., Rosel- lini, A. J., . . . Bossarte, R. M. (2017). Developing a practical suicide risk prediction model for targeting high-risk patients in the Veterans Health Administration. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 26(3). doi:10.1002/mpr.1575

14. Poulin, C., Shiner, B., Thompson, P., Ve- pstas, L., Young-Xu, Y., Goertzel, B., … Mcallister, T. (2014). Predicting the risk of suicide by analyzing the text of clinical notes. PLoS ONE, 9(1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085733

15. Allen, N. B., Nelson, B. W., Brent, D., & Auerbach, R. P. (2019). Short-term prediction of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adolescents: Can recent developments in technology and computational science provide a breakthrough? Journal of Affective Disorders, 250, 163–169. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.044

16. Bernecker, S. L., Zuromski, K. L., Gutierrez, P. M., Joiner, T. E., King, A. J., Liu, H., … Kessler, R. C. (2018, December). Predicting suicide attempts among soldiers who deny suicidal ideation in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Behaviour Research and Therapy. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.018

17. Gradus, J. L., King, M. W., Galatzer-Levy, I., & Street, A. E. (2017). Gender Differences in Machine Learning Models of Trauma and Suicidal Ideation in Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(4), 362–371. doi:10.1002/jts.22210

18. Jaroszewski, A. C., Morris, R. R., & Nock, M. K. (2019). Randomized controlled trial of an online machine learning-driven risk assessment and intervention platform for increasing the use of crisis services. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(4), 370–379. doi:10.1037/ccp0000389

19. Vaiva, G., Walter, M., Arab, A. S., Courtet, P., Bellivier, F., Demarty, A. L., … Libersa, C. (2011). ALGOS: The development of a randomized controlled trial testing a case management algorithm de- signed to reduce suicide risk among suicide attempters. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1).

doi:10.1186/1471-244x-11-1

20. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2018, June). Facts about veteran suicide: June 2018. Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/FINAL_VA_OMHSP_Suicide_Prevention_Fact_Sheet_508.pdf

21. Holder, K. A. (2017, January). Veterans in rural America: 2011–2015. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2017/acs/acs-36.pdf

22. Hom, M. A., Stanley, I. H., & Joiner, T. E. (2015). Evaluating factors and interventions that influence help-seeking and mental health service utilization among suicidal individuals: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 28–39. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.006

23. Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., Sampson, N. A., Jin, R., Druss, B., Wang, P. S., … & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine, 41(8), 1751–1761. doi:10.1017/s0033291710002291

24. Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002, February). Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry, 1, 16–20. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1489832/

25. Vogt, D. (2011). Mental health-related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: A review. Psychiatric Services, 62(2), 135–142. doi:10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0135

26. Zinzow, H. M., Britt, T. W., Pury, C. L., Raymond, M. A., Mcfadden, A. C., & Burnette, C. M. (2013). Barriers and facilitators of mental health treatment seeking among active-duty Army personnel. Military Psychology, 25(5), 514–535. doi:10.1037/mil0000015

27. Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59(7), 614–625. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.59.7.614

28. Pattyn, E., Verhaeghe, M., Sercu, C., & Bracke, P. (2014). Public stigma and self-stigma: Differential association with attitudes toward formal and informal help seeking. Psychiatric Services, 65(2), 232–238. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201200561

29. Pietrzak, R. H., Johnson, D. C., Gold- stein, M. B., Malley, J. C., & Southwick, S. M. (2009). Perceived stigma and barriers to mental health care utilization among OEF-OIF veterans. Psychiatric Services, 60(8), 1118–1122. doi:10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1118

30. Ho, T., Hesse, C. M., Osborn, M. M., Schneider, K. G., Smischney, T. M., Carlisle, B. L., Beneda, J. G., & Schwerin, M. J. (2018, July). Mental Health and Help-Seeking in the U.S. Military: Survey and Focus Group Findings (PERSERECTR_18-10, OPA-2018-048). Department of Defense, Defense Personnel and Security Research Center, Office of People Analytics. Retrieved from https://www.dhra.mil/Portals/52/Documents/perserec/reports/TR-18-10%20Estimating%20and%20Understanding%20the%20NonHelp%20Seeking%20Population%20in.pdf

31. Bryan, C. J., Jennings, K. W., Jobes, D. A., & Bradley, J. C. (2012). Understanding and Preventing Military Suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 16(2), 95–110. doi:10.1080/13811118.2012.667321

32. Bossarte, R., Claassen, C. A., & Knox, K. (2010). Veteran Suicide Preven- tion: Emerging Priorities and Opportunities for Intervention. Military Medicine, 175(7), 461–462. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-10-00050

33. Mercado, J.E., & Spain, R.D. (2014, July). Evaluating Mobile Device Ownership and Usage in the U.S. Army: Implications for Army Training (Research Report #1974). United States Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. Retrieved from https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a603886.pdf

34. Mcinnes, D. K., Fix, G. M., Solomon, J. L., Petrakis, B. A., Sawh, L., & Smelson, D. A. (2015). Preliminary needs assessment of mobile technology use for healthcare among homeless veterans. PeerJ, 3. doi:10.7717/peerj.1096

35. Looks, M. (2007, July). Meta-optimizing semantic evolutionary search. Proceedings of the 9th Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation. Retrieved from https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=1276958.1277086