Summary

The increasing sophistication and frequency of cyber incidents targeting U.S. infrastructure highlight an urgent need for a unified cyber response that bridges Homeland Security (HS) and Homeland Defense (HD). The National Guard’s (NG’s) Cyber Protection Teams (CPTs) are uniquely positioned to enhance continuity across this spectrum by operating flexibly under both HS and HD authorities and collaborating through Civil Support (CS) and Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA).

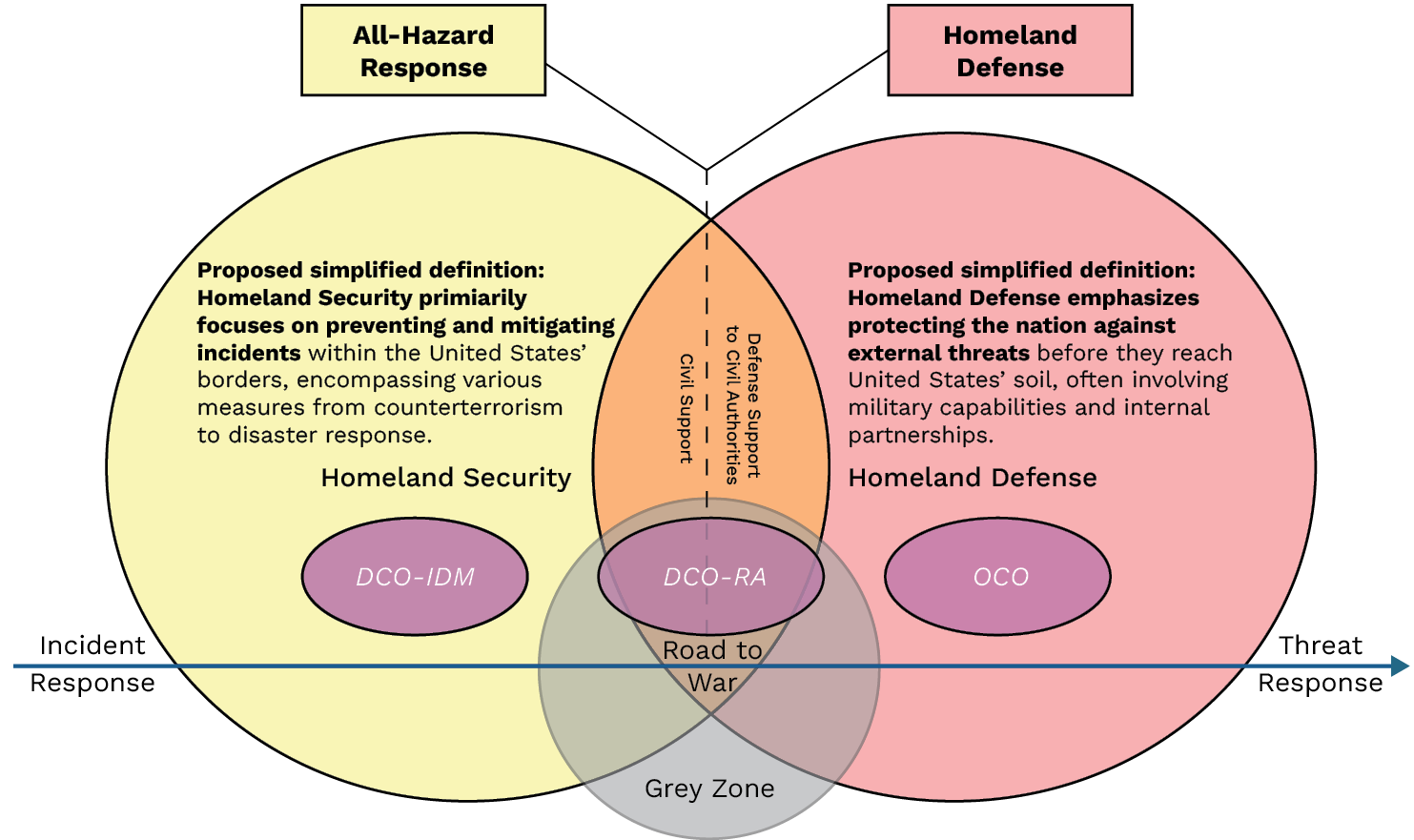

This article examines key definitions—Homeland, HS, HD, CS, and DSCA—and introduces the “Response Spectrum” model, illustrating the progression from HS-led incident response to HD-led threat response. Additionally, it outlines the U.S. Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) cyberspace operations structure, including Defensive Cyberspace Operations–Internal Defensive Measures (DCO-IDM), Defensive Cyberspace Operations–Response Actions (DCO-RA), and Offensive Cyberspace Operations (OCO), to propose a cohesive cybersecurity strategy. By reinforcing coordination among civilian and military entities, the United States can build a resilient cybersecurity posture prepared to respond to various threats, ensuring comprehensive protection and national resilience in the evolving cyber domain.

Enhancing Continuity Across HS and HD

Cyber resilience has become a critical component of national security in today’s complex and interconnected threat landscape. The increasing frequency and sophistication of cyber incidents targeting U.S. infrastructure highlight the need for a coordinated response across federal, state, and local levels. This response must involve HS and HD, which have traditionally operated under separate mandates yet now face converging challenges in the cyber domain. The NG’s CPTs present a unique opportunity to strengthen continuity and effectiveness across a spectrum of cyber responses due to their flexibility to operate under both HS and HD authorities and their capacity to integrate with public-private partnerships. These capabilities enable the NG to bridge the gap between civilian and military responses and support resilience through DSCA.

This article first clarifies the definitions of critical terms essential to understanding the distinct but overlapping roles in cyber operations: Homeland, HS, HD, CS, and DSCA. It then explores the concept of a “Spectrum of Response” that illustrates the progressive transition from incident response (HS-led) to threat response (HD-led) and how CS and DSCA serve as critical links in this continuum. Examining these roles and responsibilities can gain a better understanding of how the NG, under its unique state active duty (SAD) and U.S. Code Title 32 authorities [1], can operate effectively within civilian and military frameworks.

Furthermore, this article delves into the U.S. Joint Doctrine’s definitions of security, defense, and offense, offering insights into the structured approach to cyberspace operations. The DoD categorizes these operations into DCO-IDM, DCO-RA, and OCO, which together form a comprehensive strategy for cyberspace resilience. These elements are crucial to building a cybersecurity posture adaptable to various threats while maintaining interagency cooperation, robust communication channels, and rapid-response capabilities.

Through this detailed examination of roles, responsibilities, and strategies, the article underscores the importance of DSCA and CS in fostering a unified approach to cybersecurity. By enhancing coordination between civilian agencies and military assets, prioritizing continuous training and intelligence sharing, and leveraging NG capabilities under SAD and Title 32, the United States can significantly improve its readiness to confront cyberthreats, ensuring the nation’s security and resilience across a spectrum of potential crises.

Definitions

To truly understand the complexity of cybersecurity, it is necessary to review definitions of key concepts and explain their meanings, beginning with Homeland, HS, and HD.

The Homeland is “the physical region that includes the continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii, United States territories, and surrounding territorial waters and airspace” [2].

HS is “a concerted national effort to prevent terrorist attacks within the United States and to reduce our vulnerability to terrorism, major disasters, and other emergencies” [3].

HD refers to “the military protection of U.S. sovereignty and territory against external threats and aggression or, as directed by the President, other threats” [3].

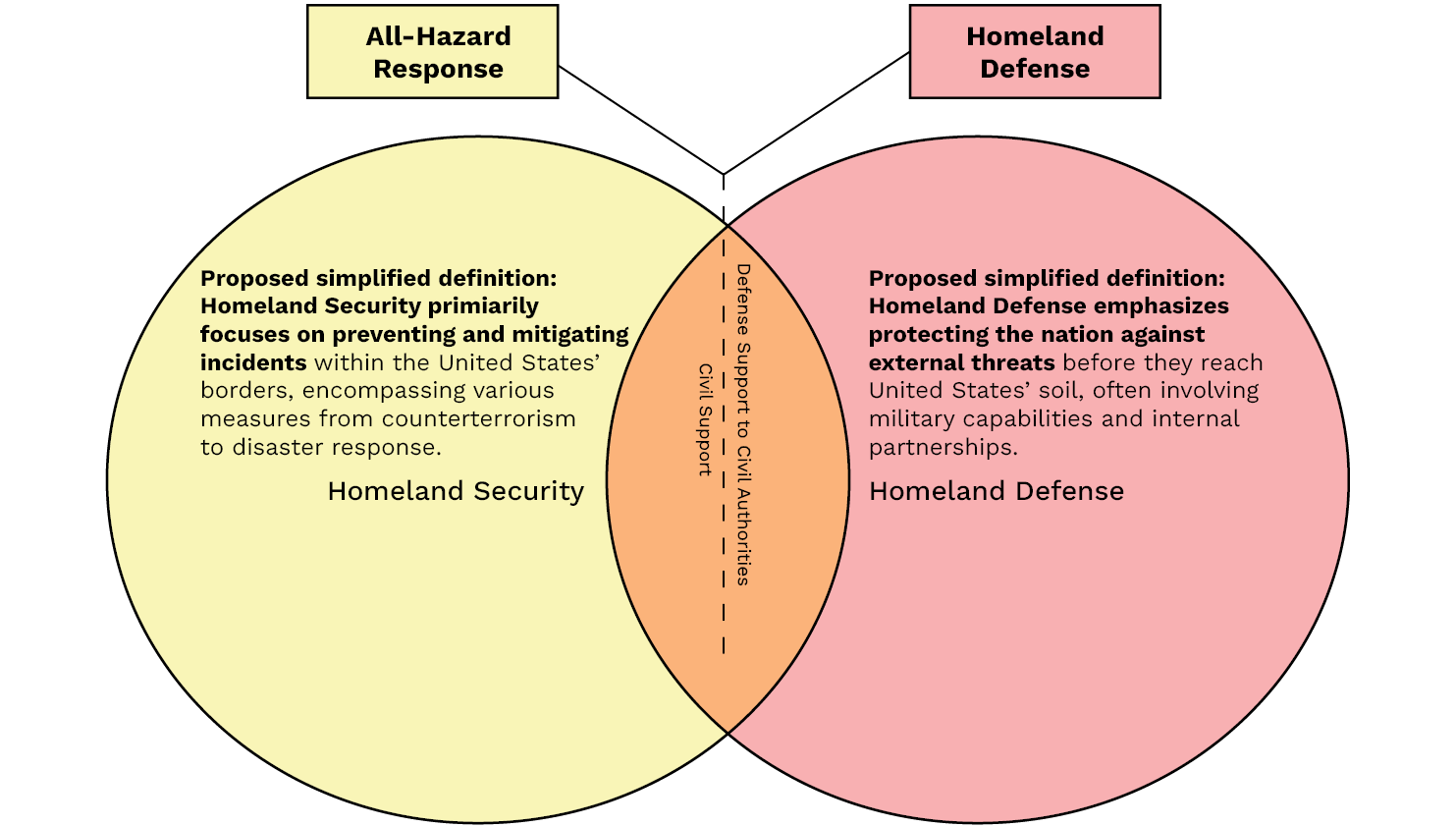

However, this article introduces the following HS vs. HD simplified definitions, as proposed by the author:

- HS primarily focuses on preventing and mitigating incidents within the United States’ borders, encompassing various measures from counterterrorism to disaster response.

- HD emphasizes protecting the nation against external threats before or once they reach U.S. soil, often involving military capabilities and international partnerships.

CS encompasses the NG’s (Title 32) and State Guards’ (SAD) support to state to local civil authorities for domestic incidents like natural or artificial disasters, terrorism, and other emergencies.

DSCA provides a formal structure allowing federal military assets under U.S. Code Title 10 [4] to support civilian agencies in emergencies, including cyber incidents. Under DSCA, federal military forces can be deployed at the request of civil authorities to address domestic threats [2]. While DSCA focuses on immediate response needs, CS includes ongoing collaboration and supports long-term civilian resilience through capacity-building, training, and infrastructure security [5].

Imagine two overlapping circles. Label one circle “Homeland Security (HS)” and the other “Homeland Defense (HD).” In the area where the circles overlap, write “Civil Support (CS)” and “Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA)” to illustrate how CS and DSCA exist where HS and HD intersect. This visual demonstrates how HS and HD contribute to the nation’s security and defense. CS and DSCA are critical components bridging these domains during domestic emergencies and crises. Though there is an overlap between “All Hazard Response” and “Persistent Attack on Homeland (Homeland Defense)” there is a point of transition for the decision (see the dashed line in Figure 1).

Figure 1. HS and HD Interactions (Source: P. Boling).

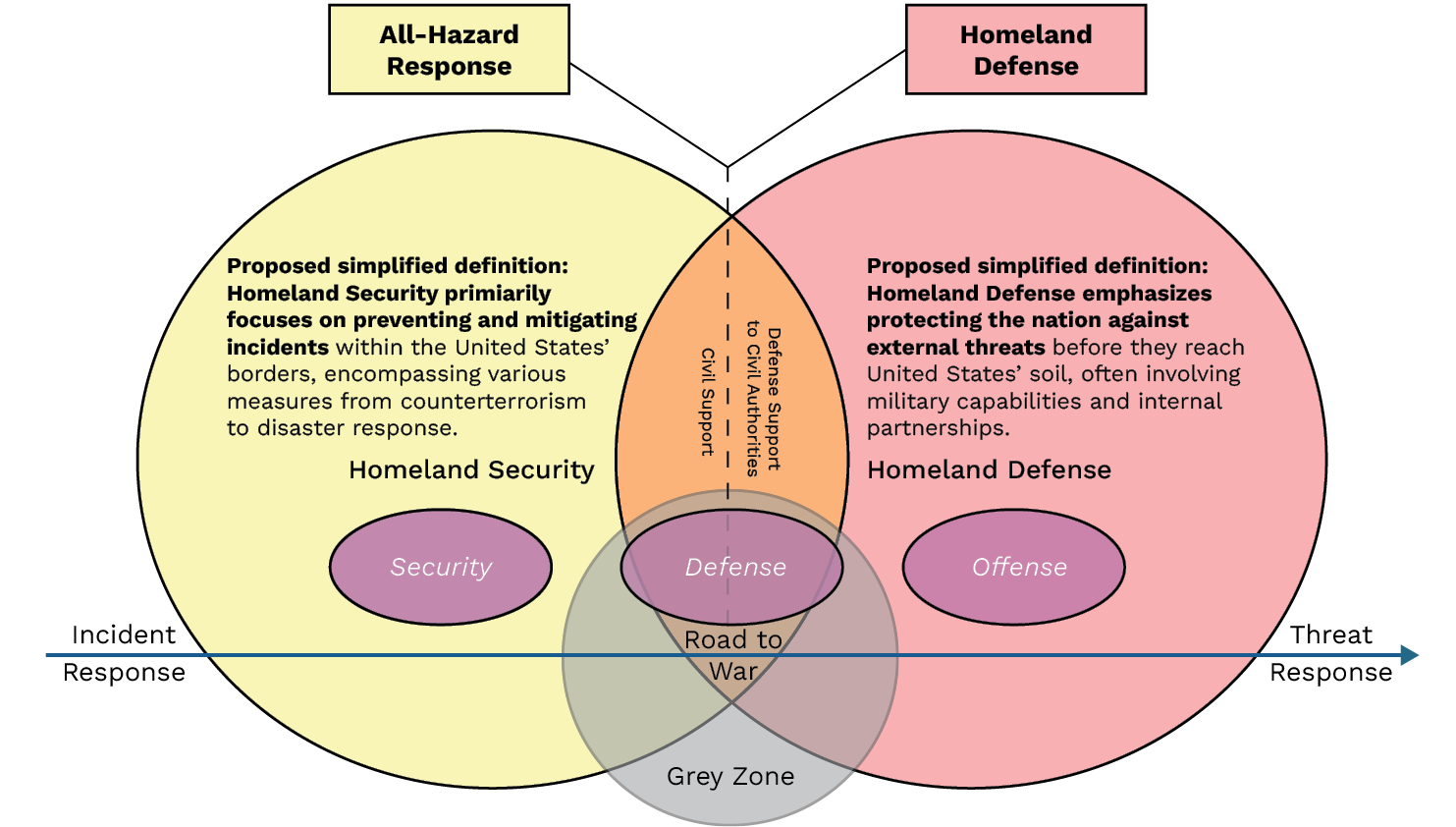

Spectrum of Response

The introduction of a concept referred to as the “Spectrum of Response” illustrates the progressive transition from incident response to threat response. The Spectrum of Response considers that a hostile act may not initially start as an apparent threat, and, therefore, the initial reaction might be an incident response. Threats conducting grey zone activities may successfully disguise an attack and delay the response necessary to neutralize the threat. Beginning with the broader U.S. Joint Doctrine, outside of the specific context of cyberspace, the terms security, defense, and offense are defined with broader military applications in mind.

In military doctrine, security refers to measures a military force takes to protect itself against threats like espionage, sabotage, attack, and surprise. Security includes safeguarding troops, installations, activities, and information from hostile actions and influences. This concept is central to military operations, ensuring that forces can operate effectively without undue interference from adversarial actions [6].

In military terms, defense employs all available means and methods to avoid or minimize damage from enemy actions and counter or defeat hostile forces. Defensive operations are undertaken to protect personnel, equipment, and designated areas from threats, thus enabling freedom of maneuver and resilience against attacks [7]. Active and passive defensive operations are conducted to repel or neutralize enemy attacks, buy time, conserve resources, or create conditions favorable for future offensive actions.

Offensive operations are actions taken to impact an enemy’s operational capability or influence other strategic aspects of the conflict, aiming to achieve national or coalition objectives. Offense focuses on direct engagement to disrupt or neutralize enemy forces, seizing control, and asserting dominance in contested areas [8]. Offensive operations are designed to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative, defeating or destroying enemy forces, gaining territory, and imposing the commander’s will upon the enemy.

Considering these definitions and how the U.S. military conceptualizes its operations in traditional warfare settings, these operations focus on physical engagements, territorial control, and direct application of force. They are foundational to military strategy, guiding how forces are organized, trained, and employed in various combat scenarios. The Spectrum of Response provides a framework for moving along a road to war and accounting for how ambiguity delays the focus transition across security, defense, and offense. While the offense waits for the threat to be identified and based on what a potential adversary may seek to exploit in the grey zone (see Figure 2), the defense can start early.

Figure 2. HS and HD Interactions With Security, Defense, and Offense (Source: P. Boling).

Integrating HS, HD, DSCA, and CS for Cybersecurity Resilience

The complex and rapidly evolving cyberthreat landscape requires a coordinated response involving civilian and military capabilities. HS and HD are two distinct but interconnected frameworks for addressing national security needs, with DSCA and CS doctrines providing critical support during cyber emergencies. This article examines the roles of HS, HD, DSCA, and CS within cybersecurity, proposing a unified approach to bolster national resilience.

Understanding cybersecurity’s role within national security requires clarifying the distinctions between HS, HD, DSCA, and CS. Led by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), HS is the primary federal agency responsible for protecting the United States from various threats, including cyberattacks. It focuses on mitigating and responding to threats within U.S. borders, including counterterrorism and disaster response. Led by the DoD, HD protects U.S. sovereignty and territory from external threats, including cyber adversaries.

Interplaying HS, HD, DSCA, and CS in Cybersecurity

In the cyber domain, HS and HD face overlapping challenges that demand coordinated efforts to defend critical infrastructure from internal and external cyberthreats. Cyberspace is a “global domain within the information environment consisting of interdependent information technology networks” [9], making it susceptible to foreign and domestic actors.

Cyberthreats targeting critical infrastructure blur the boundaries between HS and HD, requiring the integration of DSCA and CS to support immediate response and long-term cybersecurity resilience. The DoD’s National Defense Strategy [10] highlights HD as a top priority, emphasizing the need to synchronize with HS to address complex cyberthreats. Including CS within this framework adds depth by focusing on sustained support and capacity building for civilian agencies. This includes providing ongoing training, sharing best practices, and assisting in developing robust cybersecurity policies—all reinforcing the resilience of HS-led efforts over time.

Translating Doctrinal Language to Cyberspace Operations

According to Joint Publication (JP) 3-12 [9], the correct doctrinal terms for cyberspace security, defense, and offense operations within the DoD are defined in Figure 3.

![Figure 3. Cyberspace Security, Defense, and Offense Operations (Source: JP 3-12 [9] and Canva).](https://hdiac.dtic.mil/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/boling-figure-3.png)

Figure 3. Cyberspace Security, Defense, and Offense Operations (Source: JP 3-12 [9] and Canva).

These terms reflect the structured approach to both defensive and offensive cyber operations as delineated in JP 3-12, with each term specifically addressing different aspects of cyberspace operations. This doctrinal language provides a clear framework for categorizing and conducting cyber operations within the DoD, helping integrate them effectively with HS, HD, CS, and DSCA efforts.

This triad of DCO-IDM, DCO-RA, and OCO enables a comprehensive approach to achieving and maintaining security in various domains, particularly in the increasingly contested cyber domain (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. HS and HD Interactions With Defensive and Offensive Cyber Operations (Source: P. Boling).

Strategies for Integrated Cybersecurity Using DSCA and CS

Strengthening CS and DSCA for Cybersecurity Resilience

CS and DSCA must work together to bolster immediate response capabilities and long-term defense strategies to achieve robust cybersecurity. CS provides a foundation for sustained collaboration, where DoD assets and expertise support civilian agencies beyond emergencies. States can enhance interagency coordination with DHS and federal agencies through CS, integrating defense capabilities into cybersecurity preparedness frameworks.

Conversely, DSCA enables immediate deployment of military resources during cyber crises. For example, NG CPTs activated during the 2020 elections exemplified DSCA in action, supporting state and local authorities in safeguarding election systems. By establishing robust DSCA and CS frameworks, the DoD can respond effectively to cyber emergencies while enhancing civilian agencies’ preparedness through continuous training and resource allocation.

Integrating CS With NG Cyber Capabilities

Under SAD and Title 32, NG personnel operate under the authority of the state governor. They are mobilized for state missions, such as natural disaster response or civil support, and are funded by the state. The SAD status allows the NG to directly support local government agencies, including cybersecurity assistance, while aligning with state laws. In SAD status, personnel are not restricted by the Posse Comitatus Act [11] because personnel are not federalized; in their Title 32 status, they are under the authority of the State and thus allowed to support law enforcement.

Title 32 allows NG units to operate under state authority with federal funding, making them critical players in CS and DSCA efforts. This authority enables NG units to conduct cyberspace defense activities for crucial infrastructure while remaining under state control and complying with federal and state laws. The NG’s unique status allows for rapid deployment during crises (DSCA) while supporting ongoing cybersecurity training and preparedness (CS) through coordinated efforts with civilian agencies. Unlike SAD and Title 32, Title 10 status restricts Guard members from direct law enforcement activities due to Posse Comitatus limitations.

Under Title 10, NG members are federalized, operating under the authority of the President and the DoD. In this status, personnel are fully integrated with active-duty forces, allowing them to participate in national defense missions, including offensive and defensive cybersecurity operations. U.S. Code Title 50 [12] authority is generally exercised in a federalized (Title 10) context and in close collaboration with intelligence agencies.

This article does not discuss Title 50 in detail, but a potential consideration is using NG CPTs under Title 50. Title 50 provides a legal framework for the NG’s involvement in national security-related cyber missions, typically when intersecting with intelligence gathering, covert activities, or classified defense strategies. While not traditionally associated with the NG’s operational statutes, Title 50 does provide a legal framework for the Guard’s involvement in national security-related cyber missions.

Operationalizing NG CPTs With HS, HD, DSCA, and CS

Under the CS and DSCA frameworks, NG cyber units can participate in joint training exercises with DHS, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and private sector partners, bolstering interagency cooperation and cybersecurity readiness relationships that can be critical in future cyber incidents. These exercises improve real-time communication, develop shared protocols, and build capability.

The NG CPT’s ability to work across SAD, Title 32, and Title 10 statuses positions it as a versatile asset for cybersecurity within the CS and DSCA frameworks. NG units can contribute significantly by conducting infrastructure assessments, facilitating information-sharing initiatives, and providing cybersecurity education to communities. NG CPTs can sign Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) with civil, private, and industry partners and maintain continuity and confidentiality across the incident and threat response spectrum. These activities bolster the cybersecurity posture of both HS and HD, effectively reducing the nation’s vulnerability to cyber incidents and enhancing overall resilience [13].

Lt. Col. McKinney recommends using outlines of the pressing need for clear authority and structure within the U.S. Air National Guard to address cyberattacks on U.S. critical infrastructure [14]. Current legislation limits the NG’s capability to prepare for and respond to cyberthreats in Title 32 (state-level) status, even though it is involved in other domestic operations and military alert programs. Policymakers should create legislation that would empower the NG to operate in cyberspace effectively, paralleling its active support roles in different areas like the U.S. Coast Guard’s Maritime Operational Threat Response and NG’s counter-drug support, wildfire suppression, and air defense.

Multiple stakeholders, including the President, the DoD, DHS, and Congress, underscore the urgency of strengthening cybersecurity efforts. They seek to protect digital infrastructure, recognizing cyberthreats as one of the most significant challenges to national security. Recommendations emphasize legal changes to integrate NG cyber forces in domestic cybersecurity and collaborate with DHS, United States Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM), FBI, and state agencies. Implementing these measures would ensure NG cyber forces can defend critical public and private infrastructure nationally.

Integrating Offensive and Defensive Cyber Measures

Offensive and defensive cyberspace operations are integral to HD and HS. USCYBERCOM coordinates these efforts with the DoD, DHS, and other federal agencies to enhance the nation’s cyber resilience. These agencies ensure operational readiness by conducting joint training and exercises, enabling swift responses to cyber incidents. Through coordinated DCO-RA, DCO-IDM, and OCO, HS, HD, DSCA, and CS can build a comprehensive defense posture.

Laws governing military actions within the United States also apply to cyberspace, limiting DoD operations to gray and red cyberspace (neutral and adversarial networks) unless DSCA permits otherwise. These regulations ensure that DoD involvement respects civil liberties while providing critical support to civilian agencies when necessary.

Recommendations for Strengthening Cybersecurity Through DSCA and CS

The shift from HS to HD marks a critical transition from a primarily civilian-led approach to a more integrated framework involving civilian and military assets. This shift requires states to adapt by enhancing coordination between civilian agencies and the military, fostering interoperability, and establishing clear lines of communication and command to ensure effectiveness during crises. Such strategies are feasible and essential for strengthening the country’s collective security and defense. By investing in joint training exercises, sharing intelligence, and conducting collaborative risk assessments, states can significantly enhance their ability to respond effectively to a wide range of threats, creating a more resilient defense posture across the spectrum of security and defense challenges.

To effectively enhance cybersecurity resilience through CS, states must develop comprehensive plans that clearly outline procedures for integrating DoD support into routine cybersecurity activities. These CS plans should prioritize continuous training, regular risk assessments, and robust intelligence-sharing mechanisms between civilian agencies and the DoD. By doing so, states can create well-prepared, unified, proactive response frameworks to address evolving cyberthreats [15].

Adequate DSCA and CS rely on robust communication networks to facilitate real-time threat intelligence sharing across federal, state, and local agencies. Establishing liaison officers and interagency planning cells and conducting regular tabletop exercises under the CS framework are essential to strengthening these networks. These practices ensure critical information flows seamlessly between agencies, enhancing coordination and response capabilities during routine operations and crises [16].

The NG CPTs are uniquely positioned to support cybersecurity across SAD, Title 32, and Title 10 statuses, making them a versatile asset within CS and DSCA. NG CPTs play a vital role by conducting infrastructure assessments, sharing critical information, and educating communities about cybersecurity. They can engage with private industry through NDAs, ensuring confidentiality and continuity in response efforts and thereby strengthening both HS and HD. Current legislation limits NG’s ability to respond to cyberthreats in Title 32 status. However, policymakers are urged to empower the NG to operate effectively in cyberspace, similar to support roles like counter-drug operations and wildfire suppression. Strengthened collaboration with DHS, USCYBERCOM, and the FBI is recommended to enhance NG’s capability to defend critical national infrastructure from cyberthreats.

Conclusions

The evolving cyberthreat landscape necessitates an integrated and adaptable approach to national cybersecurity resilience. By leveraging the NG CPTs within the framework of both HS and HD, the United States can create a coordinated cyber response that can operate effectively across federal, state, and local levels. This capability is further enhanced by the flexibility of the NG to operate under Title 32 and Title 10 authorities, bridging the civilian-military divide and facilitating essential public-private partnerships that reinforce cyber resilience.

The comprehensive examination of key concepts like Homeland, HS, HD, CS, and DSCA illustrates the critical overlap between HS and HD and the importance of clear, unified definitions within doctrine.

This article’s Spectrum of Response model, which spans from HS-led incident response to HD-focused threat response, emphasizes the progressive shift required to address increasingly ambiguous and sophisticated cyberthreats. Utilizing established definitions of security, defense, and offense, as well as cyberspace-specific doctrines like DCO-IDM, DCO-RA, and OCO, provides a structured approach for preventative and responsive measures.

Ultimately, by strengthening the synergy between DSCA and CS, prioritizing interagency coordination and communication, and harnessing the unique capabilities of the NG under SAD, Title 32, and Title 10, the United States can significantly enhance its cybersecurity posture. A robust, unified response framework improves immediate crisis response capabilities and fosters a long-term commitment to building resilient civilian infrastructures. As the cyber domain continues to evolve, such a proactive and coordinated strategy will be essential to protecting national security interests and ensuring a resilient defense against an increasingly complex spectrum of cyberthreats.

References

- U.S. House of Representatives. U.S. Code Title 32 – National Guard, 10 August 1956.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. “JP 3-28: Defense Support of Civil Authorities.” Washington, DC, 17 April 2018.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. “JP 3-27: Homeland Defense.” Washington, DC, 29 November 2021.

- U.S. House of Representatives. U.S. Code Title 10 – Armed Forces, July 2011.

- Jackson, B. A. “The Role of the U.S. Department of Defense in Domestic Disaster Response: Legislative Evolution and Issues for Congress.” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. “JP 3-10: Joint Security Operations in Theater.” Washington, DC, 13 November 2014.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. “JP 3-0: Joint Operations.” Washington, DC, 17 January 2017.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. “JP 3-09: Joint Fire Support.” Washington, DC, 10 December 2019.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. “JP 3-12: Cyberspace Operations.” Washington, DC, 8 June 2018.

- U.S. DoD. “2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America.” Washington, DC, 2022.

- U.S. Congress. Posse Comitatus Act, 15 June 1878.

- U.S. House of Representatives. U.S. Code Title 50 – War and National Defense, 2011.

- Jensen, E. T. “Cyber Sovereignty: The U.S. Perspective and the Implications for National Guard Cyber Operations.” Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2020.

- McKinney, Lt. Col. M. M. “A National Solution: Rethinking the Employment of Air National Guard Title 32 Status Citizen-Airmen to Defend the Nation’s Cyberspace Infrastructure.” Unpublished research paper, Air War College, Maxwell Air Force Base, AL, 2013.

- Brenner, S. W. “Cyberthreats: The Emerging Fault Lines of the Nation State.” New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Lin, H. S., and A. B. Zegart, eds. Bytes, Bombs, and Spies: The Strategic Dimensions of Offensive Cyber Operations. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2019.

Bibliography

Ferguson, A. T. “Closing the Gaps: Cybersecurity for U.S. Forces and Commands.” Ph.D. dissertation, Joint Forces Staff College, Joint Advanced Warfighting School, 2017.

OpenAI. ChatGPT [Large language model], https://chatgpt.com, 2024.

xAI. Grok. AI Chatbot, https://x.com/i/grok, 2024.

Biography

Patrick O’Brien Boling, a recent graduate of the Joint Combined Warfighting School, serves as Deputy for the J7 Plans, Exercises, and State Partnership Program Division in the Louisiana National Guard. He has served in a variety of joint, strategic, operational, and tactical assignments in the U.S. Army and National Guard as a field artillery officer and infantry officer. LTC Boling holds an M.S. in management of engineering from Louisiana Tech University, an M.S. in administration of justice and security from the University of Phoenix, and a Ph.D. in organizational management from Capella University.