Introduction

When the first transaction was posted on the Bitcoin blockchain in 2009, a worldwide paradigm shift began that would not fully come to fruition until almost a decade later. As cryptocurrency was slowly evolving into an investment zeitgeist with Bull and Bear markets, the adoption of cryptocurrencies as payments in illicit circles had been status quo long before the layperson believed they could make money trading it. Perhaps the most famous of cases would be the “Silk Road” marketplace and how Bitcoin was the backbone of the dark-web ecosystem. While dark‑web-sourced contraband was, and still is, a scourge on society, terrorist organizations began to incorporate cryptocurrencies as part of their financing networks in tandem with the rise of dark‑web drugs. Cryptocurrencies remain a persistent medium for the fiduciary networks that enable terrorism around the world. Figure 1 depicts an Al Sadaqah Bitcoin donation campaign.

Figure 1. Al Sadaqah Donation Campaign (Source: U.S. Department of Justice [DOJ] [1]).

Adopting Cryptocurrencies as Donations

The earliest-reported foreign terrorist organization that adopted cryptocurrencies as a means of donations was the Ibn Taymiyyah Media Center (ITMC) crowdfunding campaign for Mujahideen Shura Council/Environs of Jerusalem in 2016 (Figure 2) [2]. Dubbing the crowdfunding campaign “Jahezona” (Arabic for “Equip Us”), ITMC informed tentative donors that the Bitcoin funds would be used to purchase weapons. The Jahezona campaign ran for approximately two years, raising tens of thousands of dollars for ITMC. In a time when cryptocurrencies were still a niche interest and not as accessible as they are today, this produced a significant amount of funding and was a successful campaign by ITMC. While it is unknown if the donated Bitcoin was ever directly linked to any weapons purchased and used in Gaza, it certainly became the archetype that other terrorist organizations would copy. Figure 3 depicts other terrorist donation campaigns seeking Bitcoin.

Figure 2. Screenshot of ITMC Jahezona Campaign 2016 (Source: Chainalysis Team [2]).

Figure 3. Various Terrorist Donation Campaigns Seeking Bitcoin (Source: DOJ [1]).

Izz ad-Din Al-Qassam Brigade (AQB) 2019 Campaign

Perhaps the most well-known cryptocurrency-backed terrorism campaign was AQB in 2019. It is notable not because the campaign itself raised a significant amount of funding in Bitcoin at the time but because of the rising interest in cryptocurrencies by law enforcement and regulators around the world. In 2018, the “Financial Technology Innovation and Defense Act” [3] was introduced to Congress and world governments began to recognize the threat posed by a lack of regulation in compliance in the cryptocurrency space. During this time, AQB’s ongoing campaign consisted of various subcampaigns to “Donate to Jihad,” which showed an evolution in the tradecraft in which AQB instructed possible donors to utilize public/open Wi-Fis or virtual private networks when donating funds. Analysis of the flow of Bitcoin funds by Chainalysis [2] relating to the AQB campaign shows the eventual exposure to peer-to-peer (P2P) services and virtual asset service providers (VASPs), also known as exchanges, where the funds were converted to fiat.

2020 DOJ Disruption and Seizure

In August 2020, the DOJ announced the largest-ever disruption of cryptocurrency-facilitated terrorist financing. By dismantling the cryptocurrency donation networks for the AQB “Donate to Jihad,” as well as Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), ~$2M worth of cryptocurrency funds was also seized. A DOJ press release stated the following [1]:

These three terror finance campaigns all relied on sophisticated cybertools, including the solicitation of cryptocurrency donations from around the world. The action demonstrates how different terrorist groups have similarly adapted their terror finance activities to the cyberage. Each group used cryptocurrency and social media to garner attention and raise funds for their terror campaigns. Pursuant to judicially authorized warrants, U.S. authorities seized millions of dollars, over 300 cryptocurrency accounts, four websites, and four Facebook pages all related to the criminal enterprise.

Unequivocally the most notable seizure of the time, the urgency and need for regulation came to the forefront as the cryptocurrency furor was reaching the “mainstream.” The trajectory of cryptocurrencies had significantly changed from the “underworld” to Wall Street portfolios. Consubstantially, world powers like Iran and Russia began to adopt cryptocurrencies into their economies to avoid Western sanctions.

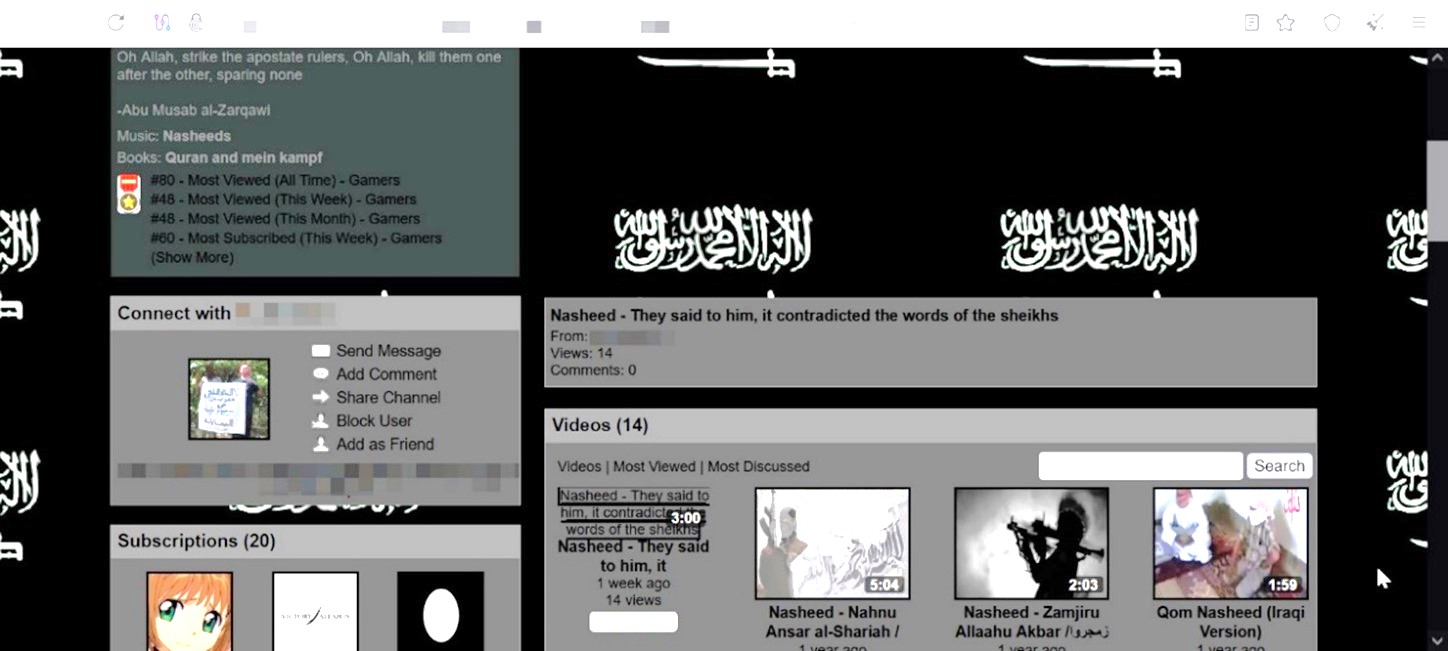

Persistent Utilization of the Dark Web and End-to-End Encryption (E2EE) Apps

In 2016, Gabriel Weinmann authored “Terrorist Migration to the Dark Web”[4]. Over eight years later in 2024, the utilization of dark-web-related services for both the hosting and propagation of terrorist content remained steadfast. However, a paradigm shift has been observed with users more comfortable utilizing various E2EE platforms outside of the dark nets. An example image of a social-media sharing platform is provided in Figure 4. Although the dark nets provide a platform for online anonymity, many users choose to provide alternative methods to communicate outside of the dark net. Figure 5 shows a social-media channel with the user stating an intention to connect with an E2EE platform Element.io.

Figure 4. Social-Media Sharing Platform (Source: VidLil [5]).

Figure 5. Dark-Net-Based Social-Media Sharing Platform With User Referring to E2EE Element.io (Source: VidLil [5]).

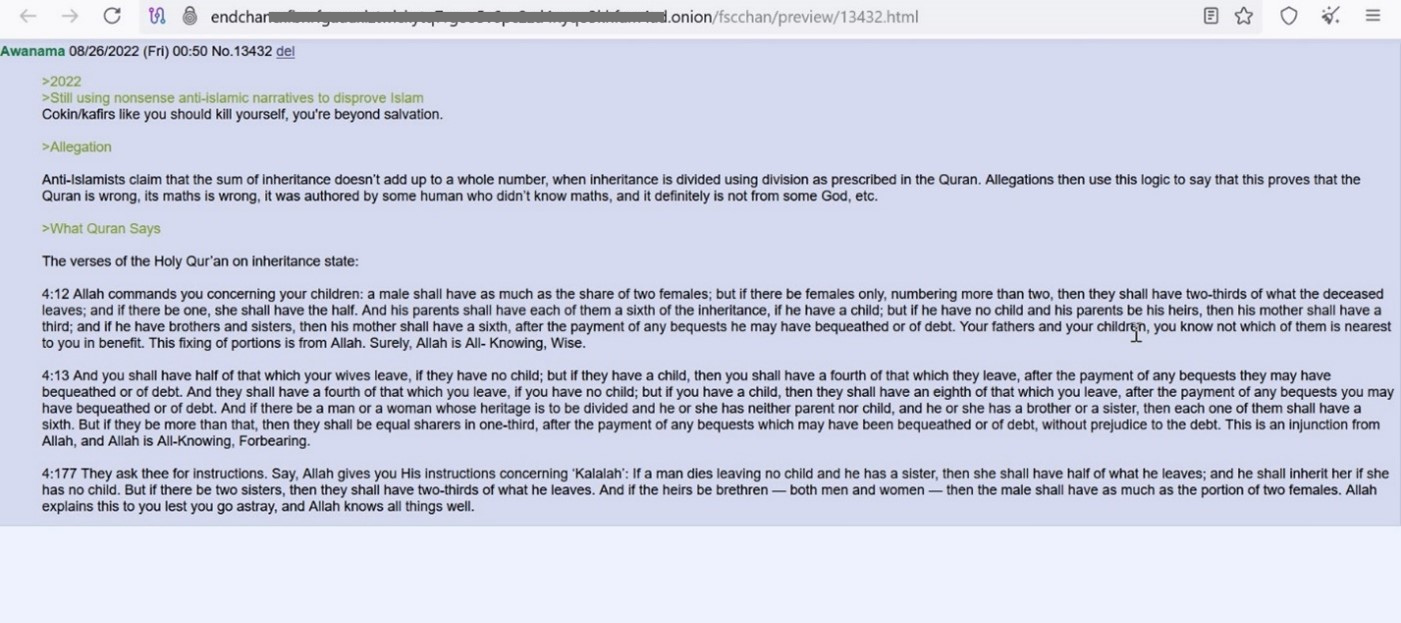

Over the past decade, many social-media platforms have proactively addressed and blocked terrorist-aligned content, leveraging evolving artificial intelligence algorithms to detect it [6]. Yet, such efforts on the dark-net platforms remain unseen. For many of the “chan-” based posting forums on the dark nets, like EndChan (Figure 6), posters need not fear censorship or any possible reporting to law-enforcement authorities.

While this has sparked a polarizing conversation on censorship and free speech, a contingency involving a dark-net migration occurred after Cloudflare removed hosting of the notorious 8Chan anonymous-posting site following the Christchurch, New Zealand mass shooting [7]. Ultimately, 8Chan found emergency hosting on the ZeroNet [8], a pseudonymous dark net built on the Bitcoin blockchain (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Posting on EndChan Dark-Net Posting Forum (Source: EndChan [9]).

Figure 7. Screenshot of 8Chan Hosted on ZeroNet; Sites Resolve to Bitcoin Wallet Addresses (Source: DarkOwl, LLC [8]).

Figure 8. Screenshot of Dark-Net-Based Terrorist News and Propaganda (Source: Mujaheddin [11]).

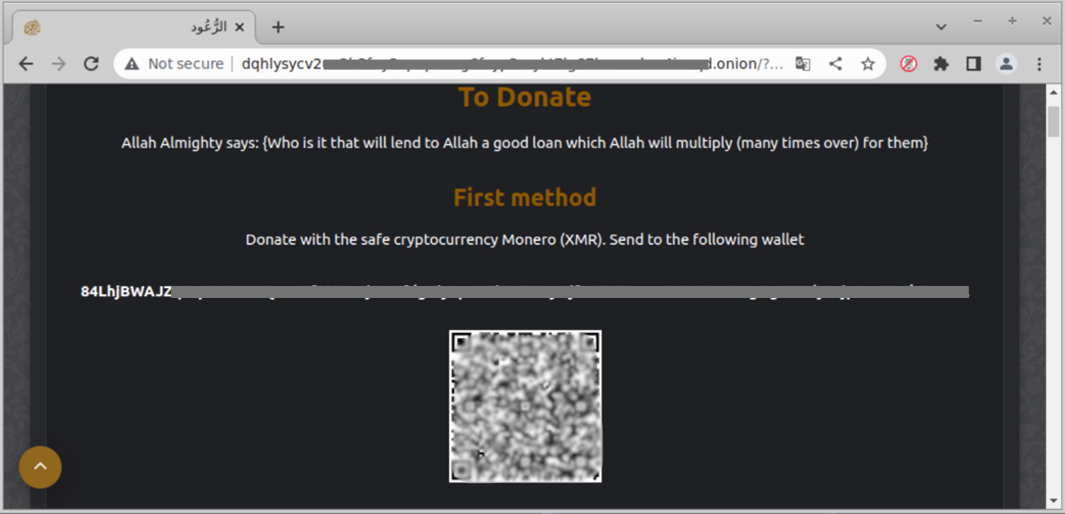

Shift From Bitcoin to Alternative Cryptocurrencies

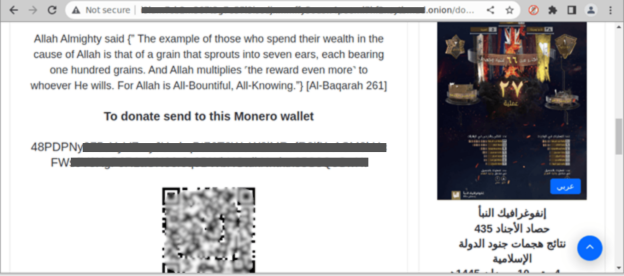

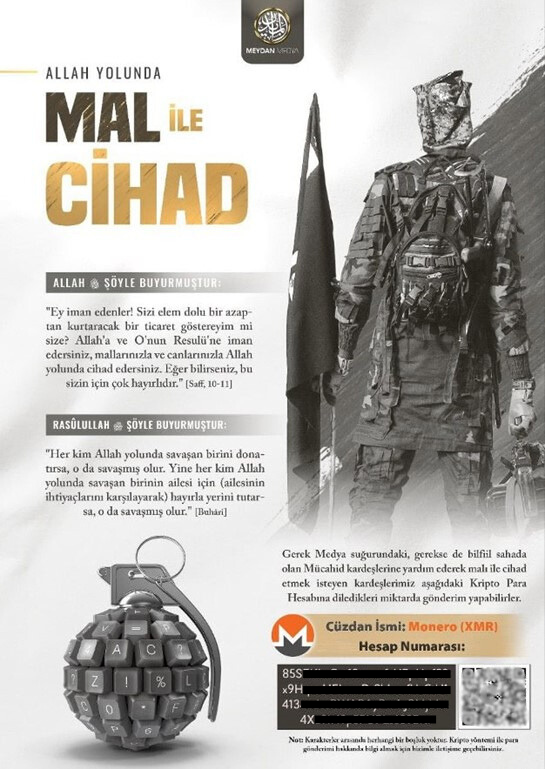

One of the ripple effects of the 2020 DOJ disruption campaign was the adoption of alternative cryptocurrencies in lieu of Bitcoin by certain terrorist organizations. Approximately two months before the announcement by the DOJ, Akhbar al-Muslimin stopped accepting Bitcoin as payment and only accepted Monero, an anonymity-enhanced coin (AEC) (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Screenshot Advertising That ISIS Transitioned to Monero for Fundraising Efforts (Source: @Whitestream [12]).

Figure 10. Screenshot of Hamas Crowdfunding Campaign (Source: Kholafaps [15]).

Figure 11. Screenshot of Dark-Net-Based Terrorist News and Propaganda Site “i3lam” (Source: i3Lam [18]).

Figure 12. Screenshot of ISIS-K “i3lam” Translation Requesting Donations in Monero Digital Currency (Source: i3lam [18]).

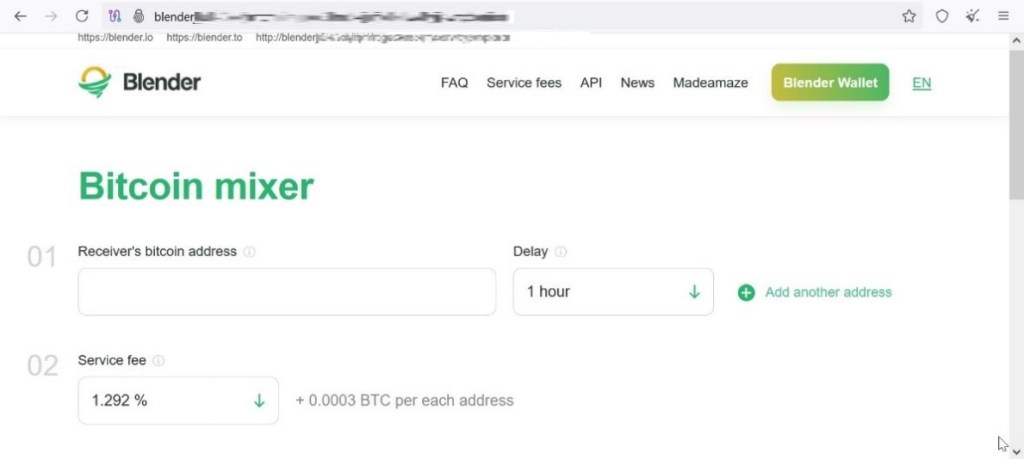

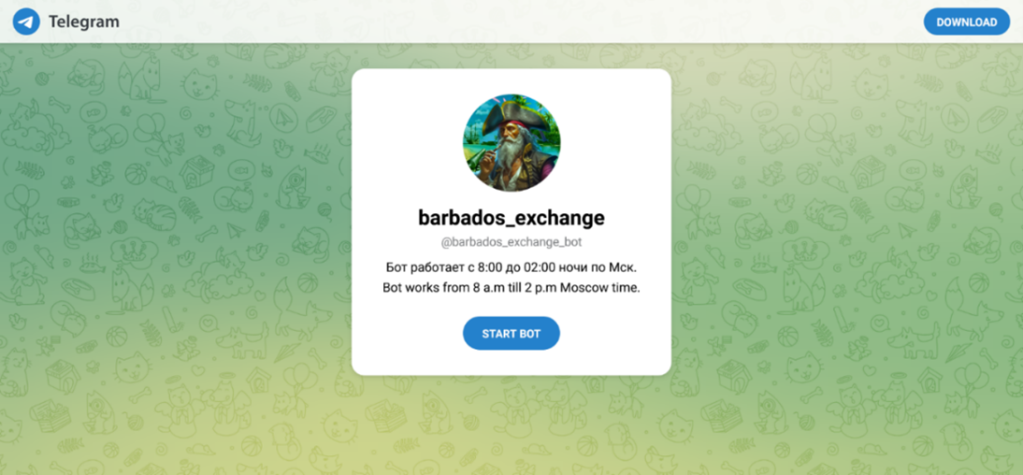

The availability of cryptocurrency-laundering services, colloquially known as “mixers,” has also become an essential component in the movement of funds to terrorist-aligned organizations or adversarial countries. One such highly publicized mixing service is “Tornado Cash,” which was sanctioned by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) in 2022 [20] but ultimately had the sanction overturned in November 2024 [21]. Mixing services remain incredibly popular on the dark web, with many services jockeying for illicit funds. While reliability and trust certainly remain a constant unknown in a space with no regulation or avenues of redress, mixing remains a key component in the movement of cryptocurrency among illicit and malevolent services. Figure 13 shows an example of a Bitcoin mixing service.

Figure 13. Screenshot of Bitcoin Mixing Service Blender on the Onion Router (Commonly Known as Tor) (Source: Blender [22]).

Figure 14. Screenshot of a Digital Currency Mixing Service Operating on Telegram (Source: Telegram [28]).

Recommendations

As cryptocurrency continually becomes intertwined and accepted by payment institutions all over the world, it will inevitably remain a constant medium in which funds are sent to terrorist organizations. As law enforcement, regulators, and nonprofit organizations diligently identify cryptocurrency wallets/services associated with terrorist funding, considerably more P2P and decentralized exchanges offer “swapping” capabilities for Monero. Swapping services like FixedFloat [29], WizardSwap [30], ChangeNOW [31], and Changelly [32] facilitate the instantaneous exchange of cryptocurrencies with little or no KYC compliance. Consequently, the operational security of the terrorist financial supporters improves in tandem with the techniques to obfuscate the flow of the funds.

Despite the increase in sophistication in how terrorist organizations move the cryptocurrencies from blockchain to blockchain, how those cryptocurrencies are converted to fiat remains the key component in identifying and disrupting terrorist financial networks. Many virtual‑wallet services that now incorporate cryptocurrencies into their payment systems (CashApp [33], Venmo [34], and Revolut [35]) lack the diligence to monitor cryptocurrency transactions that may be associated with nefarious activity, which is now beholden heavily on the fintech sector. The synchronicity of virtual wallets with exchanges/VASPs like Binance have birthed a very active P2P trading platform [36] (Figure 15). For example, the P2P market incorporates both virtual wallets and banking institutions in direct purchasing of cryptocurrencies between users, juxtaposed to the cryptocurrencies being purchased from the exchanges’ liquidity [37]. This process provides an interesting means to circumvent traditional KYC/AML compliance, whereas the exchange itself does not facilitate the purchase of the cryptocurrency but merely oversees the private transfer. With Bitcoin reaching over $100,000 in December 2024 [38], it is safe to surmise that cryptocurrency will become an immutable component of the financial sector’s future developments. With the incorporation of cryptocurrencies into payment systems, it is crucial that due diligence remain a priority from both the public and private sector to help curtail the flow of funds to terrorist organizations all over the world.

Figure 15. Binance P2P Marketplace; AED Payments Selected (Source: Binance [37]).

References

[1] U.S. Department of Justice. “Global Disruption of Three Terror Finance Cyber-Enabled Campaigns.” DOJ Archives, https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/global-disruption-three-terror-finance-cyber-enabled-campaigns, 13 August 2020.

[2] Chainalysis Team. “Terrorism Financing in Early Stages With Cryptocurrency but Advancing Quickly.” Chainalysis, https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/terrorism-financing-cryptocurrency-2019/, 17 January 2020.

[3] 115th U. S. Congress. “Financial Technology Innovation and Defense Act.” H.R. 4752, U.S. Government Publishing Office, Washington, DC, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4752/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22H.R.4752%22%5D%7D&r=1, 10 January 2018.

[4] Weimann, G. “Terrorist Migration to the Dark Web.” Perspectives on Terrorism, vol. 10, issue 3, pp. 40–44, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26297596, June 2016.

[5] VidLil. “VidLil Tor/Dark-Net Version.” Tor/Dark-web forum, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[6] Macdonald, S., S. Giro Correia, and A.-L. Watkins. “Regulating Terrorist Content on Social Media: Automation and the Rule of Law.” International Journal of Law in Context, vol. 15, special issue 2, pp. 183–197, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-journal-of-law-in-context/article/regulating-terrorist-content-on-social-media-automation-and-the-rule-of-law/B54E339425753A66FECD1F592B9783A1, June 2019.

[7] Prince, M. “Terminating Service for 8Chan.” Cloudflare, https://blog.cloudflare.com/terminating-service-for-8chan/, 5 August 2019.

[8] DarkOwl, LLC. “8Chan Activates ‘Emergency Bunker’ on Dark Net.” DarkOwl, https://www.darkowl.com/blog-content/8chan-activates-emergency-bunker-zeronet/, 7 August 2019.

[9] EndChan. “EndChan Forum.” Tor/dark-web forum, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[10] The Monero Project. “What Is Monero?” Monero, https://www.getmonero.org/, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[11] Mujaheddin. “Mujaheddin Propaganda/Translation Channel.” Tor/dark-web forum, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[12] @Whitestream. “Blockchain Intelligence.” X, https://x.com/whitestream5/status/1276113021274898434, 25 June 2020.

[13] Berwick, A., and I. Talley. “Hamas Militants Behind Israel Attack Raised Millions in Crypto.” The Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/world/middle-east/militants-behind-israel-attack-raised-millions-in-crypto-b9134b7a, 10 October 2023.

[14] Wison, T., and E. Howcroft. “Focus: New Crypto Front Emerges, Israels Militant Financing Fight.” Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/new-crypto-front-emerges-israels-militant-financing-fight-2023-11-27/, 30 November 2023.

[15] Kholafaps. “Telegram Channel Kholafaps.” Dark-web forum, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[16] Culafi, A. “Monero and the Complicated World of Privacy Coins.” TechTarget, https://www.techtarget.com/searchsecurity/news/252512394/Monero-and-the-complicated-world-of-privacy-coins, 24 January 2022.

[17] Brucker, K. “The Terrorist Attack at the Crocus City Hall in Moscow.” U.S. Mission to the OSCE, U.S. Department of State, https://osce.usmission.gov/on-the-terrorist-attack-at-the-crocus-city-hall-in-moscow/, 11 April 2024.

[18] i3lam. “i3lam Jihad Support Service.” Tor/dark-web forum, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[19] CoinChapter. “Monero’s Removal From Binance Imminent—What Happens After Delisting.” Binance Square, https://www.binance.com/en/square/post/12082270920489, 12 August 2024.

[20] U.S. Department of the Treasury. “U.S. Treasury Sanctions Notorious Virtual Currency Mixer Tornado Cash.” https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0916, 8 August 2022.

[21] Parlovecchio, G. M., J. Herring, T. A. Soliman, A. S. Hickey, J. A. Castelluccio, and B. J. Harrington. “Federal Appeals Court Tosses OFAC Sanctions on Tornado Cash and Limits Federal Government’s Ability to Police Crypto Transactions.” Mayer Brown, https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/insights/publications/2024/12/federal-appeals-court-tosses-ofac-sanctions-on-tornado-cash-and-limits-federal-governments-ability-to-police-crypto-transactions, 3 December 2024.

[22] Blender. “Blender: Bitcoin Mixer.” Tor/dark-web forum, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[23] Ledger Insights Ltd. “Telegram Reliant on Crypto Revenues.” Ledger Insights, https://www.ledgerinsights.com/report-telegram-reliant-on-crypto-revenues/, 2 September 2024.

[24] Jamali, L. “Telegram Will Now Provider Some User Data to Authorities.” BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cvglp0xny3eo, 23 September 2024.

[25] Tox. “A New Kind of Instant Messaging.” https://tox.chat/, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[26] Session Technology Foundation. “Send Messages, Not Metadata.” Session, https://getsession.org/, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[27] Stochastic Systems LLC. “PRIVI: Communicate Freely.” Privi, https://about.pri.vi/, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[28] Telegram. “Barbados Exchange.” Dark-web forum, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[29] FixedFloat. “Lightning Cryptocurrency Exchange.” https://ff.io/, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[30] WizardSwap. “Coinbase Users.” https://www.wizardswap.io/, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[31] CHN Group LLC. “Limitless Web3.0 Crypto Exchange.” ChangeNOW, https://changenow.io/, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[32] Changelly. “Exchange Any Crypto Instantly.” https://changelly.com/, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[33] Blockworks Inc. “CashApp Integrates Lightning Network of Bitcoin Payments.” Blockworks, https://blockworks.co/news/cash-app-integrates-lightning-network-for-bitcoin-payments, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[34] PayPal, Inc. “Venmo Cryptocurrency Terms and Conditions.” Venmo, https://venmo.com/legal/crypto-terms/, 21 October 2023.

[35] Revolut Ltd. “Cryptocurrency.” Revolut, https://www.revolut.com/legal/cryptocurrency-terms/, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[36] Binance. “Binance P2P: Buy Bitcoin via CashApp.” https://www.binance.com/en/blog/p2p/binance-p2p-buy-bitcoin-via-cash-app-421499824684904012, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[37] Binance. “P2P.” https://p2p.binance.com/en, accessed on 17 November 2024.

[38] Yaffe-Bellany, D. “Bitcoin Hits a Milestone: $100,000.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/04/technology/bitcoin-price-record.html, 4 December 2024.

Biography

Keven Hendricks is an 18-year law-enforcement veteran and has served as a task force officer for two separate federal agencies. He is a published author with the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, Blue Magazine, and American Police Beat and currently works as an instructor for various police training companies, teaching classes for law enforcement on dark-web and cybercrime investigations. He is a certified cybercrime examiner and certified cybercrime investigator by the National White Collar Crime Center, a certified cryptocurrency investigator through the Blockchain Intelligence Group, and a certified digital asset professional through the Global Digital Asset & Cryptocurrency Alliance. He is recognized as a subject matter expert in dark-web investigations and the founder of the Ubivis Project Stopdarkwebdrugs.com.