Introduction

According to geostrategist David Kilcullen, the next big conflict will be “urban, connected, and littoral” with adversaries, friends and neutrals exhibiting hybrid state and non-state characteristics. [1] The U.S. military will likely be involved in humanitarian or operational missions in megacities across the globe.

A disaster occurring in Lagos, Nigeria, where more than half of an estimated 20 million people live in alternately-governed slums, not only fits this description, but it would also create a scene unprecedented in its scale of devastation and confusion. [2] This study aids military planners and first responders to adapt to parts of Lagos transformed by crisis into Black Spots, a term coined by Bartos Stanislawski to denote areas “outside of effective governmental control and controlled, instead, by alternative, mostly illicit, social structures.” [3, 4] Yet, not all non-state actors are nefarious. U.S. Army Maj. Arnel David suggests that databases of local non-governmental organizations where emergencies might arise should be maintained because their assistance could significantly contribute to mission success. He further opines that “enhanced engagements and cooperation with civil society organizations increase connectivity to the local populace and create a potential capability to leverage local knowledge”; yet “military use of civilian networks in this capacity has not been explored.” [5] David’s thesis articulates why this study is significant in bridging a strategic knowledge gap about non-state actors’ roles and capacities in megacity disaster management. [6]

Background and Literature Review

Worldwide, rapid urbanization has attracted attention from various scholars. Urban populations greater than 10 million constitute the United Nations definition of a megacity. [7] Using the same population threshold, this study holds to a theory of mega-global city divergence between global cities, chiefly located in the North that coordinate complex global economic activity, and megacities, primarily located in the South with few global functions but many informal settlements (a euphemism for slums). [8] While mass urbanization elicits praise from economists for creating scores of better educated, middle class consumers, it draws ire from environmentalists over grave risks from uncontrolled and unsustainable growth. Anglophone Lagos, the economic engine of West Africa, makes an excellent case study because of its 8 percent annual growth rate, dense population and vulnerable physical geography. [9] There, numerous informal settlements ring a low-lying lagoon; thus its name from the Portuguese lago, Lagos. [10] Flooding in recent years has reached devastating proportions and Lagos’ slum dwellers have borne the brunt of “heavy rainfall combined with rising sea levels, sinking sand-filled water spaces and inadequate drainage systems.” [11, 12] Rem Koolhaas and his fellow urbanists pointed to Lagos’ pervasive informality in housing, economy and security as a future archetype where megacity populations organize themselves apart from the state. This view informed questions posed by the German authors of the Megacity Resilience Framework, which, in turn, prompted this study of disaster management in the Nigerian megacity.

Lagos’ mega traffic jams. (Image courtesy of Signal Books, Oxford, U.K./Released)

Can people rely on functioning formal institutions in case of disturbances, for instance on disaster management, relief and recovery implemented by state or city authorities in case of a natural disaster? Or do they mainly have to organize help themselves and trust in their membership in social networks to reduce their losses in such an event and secure their livelihoods thereafter? [14]

Megacities are a recent phenomenon; the term entered the literature in the late 1980s. Given the myriad of factors surrounding megacity growth and sustainability, literature is divided between the optimistic (Kalan, [15] Kourtit and Nijkamp, [16] Glaeser, [17] Khanna [18] and Barber [19]) and the ominous (Davis, [20] Castells, [21] Pieterse [22] and Setchell [23]). The over-attention to human distemper in the gloomier works, however, ignores the communal resiliency that belies the optimistic versus ominous dichotomy. The latter works seem to disregard how, in a 1990s Second Liberation of the African continent, an evolving civil society was instrumental in ousting dictators and military juntas and ushering in more democratization and development. [24] Civil society is defined here as a sphere of social life that is public, but excludes government and private business activities. [25]

Urbanization in sub-Saharan Africa has worked against consolidation of state power. As a result, its informal settlements are replete with alternatively governed spaces featuring informal policing, administration of justice and mechanisms of social control. [26] Loren Landau, director of the African Center for Migration and Society, asserts that the Africanized urban governance phenomenon is “a form of polity that we have yet to name, let alone understand.” [27] U.S. military planners are only now beginning to think about humanitarian assistance/disaster response missions in densely-populated urban areas outside the control of host nation government. [28] Moreover, U.S. intelligence community analytical portfolios are not focused on cities, even when their populations and gross domestic products are greater than many nation states. [29] To counter this lack of actionable intelligence, some, like Maj. David, call for U.S. Army stability teams in megacities to gather data on the flows of people, materials and ideas. However, it remains highly improbable that U.S. regionally aligned forces, with Boko Haram terrorism, the Ebola virus, piracy in the Gulf of Guinea and a host of security assistance difficulties to contend with, would commit resources to the comparatively stable Lagos’ impalpable informal register. [30]

Lagos in Context

While smallest in area, and no longer the seat of the national capital, Lagos is by far the most populous and progressive state among Nigeria’s 36 federated states. Lagos State, 85 percent urban and thus synonymous with the megacity, receives 6,000 new migrants daily. This “turbo urbanization” has quadrupled Lagos’ population since 1980. [31, 32] Scientists from the International Union of Geological Sciences reported the sheer scale of megacities “creates new dynamics, new complexity and new simultaneity of events and processes—physical, social and economic; [and] they host intense and complex interactions between different demographic, social, political, economic and ecological processes.” [33] The multiplicity of relationships, their uncharted flows, connectedness and contexts frustrates efforts to understand the Nigerian primate city as an operating environment. Just as byzantine connotes a situation encumbered by laborious administrative detail, a term introduced here, lagosian, embodies Edgar Pieterse’s concept of the informal register at the megacity scale. Lagosian suggests a milieu of institutions, so loosely integrated, and of power and authority brokers, so diffuse as to defy governance. Yet Lagos functions surprisingly well and boasts many recent infrastructural and administrative advances. Indeed, the Lagos State slogan under current Governor Babatunde Fashola is, in the Yoruba language, Eko O Ni Baje or Lagos Must Not Spoil. Fashola has affected significant positive change, generating the necessary revenues to fund his vision of Lagos becoming a global city. This includes Eko Atlantic, a highly-visible land reclamation project ordained to become the glitzy new financial center of West Africa. [35] However, Eko (an old Yoruba name for Lagos) Atlantic is not without its detractors who cite its negative impacts on the environment and vulnerable communities or denounce the purely elitist nature of the project. [36]

If Lagos is not to spoil, it stands to reason that its gains must be protected. To that end, coinciding with the return of civilian rule, the Nigerian Emergency Management Agency was founded in 1999, followed by state-level agencies like the Lagos State Emergency Management Agency. In Lagos State, Nigeria’s showcase for development, LASEMA conducts a range of disaster management services, from prevention and preparedness, to mitigation, recovery and relief. [37] However, its critics have derided the emergency response as “neither coordinated nor prompt enough and this has resulted in large-scale destruction and suffering of the affected people.” [38] Despite its shortcomings in disaster management and other services, Lagos’ comparative stability marks it as the destination of choice for West African migrants. [39]

An artist’s conception of the future Eko Atlantic complex. (Copyright EkoAtlantic.com 2014/Released)

In governance research on Africa, scholars have overwhelmingly concentrated not only on nation states as opposed to cities, but on obstacles to state-building rather than on prospects or methods for improving service provision. For that reason, this study focuses on affected norms of Lagosian civil society organizations that might partner in disaster management rather than bureaucratic norms of public agencies. While a very small sample size limits generalizations, survey responses and personal interviews identify and sort CSOs into the five activity rubrics that make their potential roles as implementing partners in Lagosian disaster management more comprehensible.

![Figure 1: Survey Respondents’ Organizations Classified into Five Civil Society Roles. [40] Figure 1 reflects, from 50 survey responses, the percentages among five civil society roles to which the respondents self-assigned their respective organizations.](https://hdiac.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/201509-DMgmt-Fig1-300x213.jpg)

Figure 1: Survey Respondents’ Organizations Classified into Five Civil Society Roles. [40] Figure 1 reflects, from 50 survey responses, the percentages among five civil society roles to which the respondents self-assigned their respective organizations.

Local Government Challenges

Vulnerability to natural hazards has been cited as a rationale by the Lagos State government to forcibly evict slum dwellers, ostensibly from flood-prone areas, often only to have a shopping mall or other development constructed on the same land. CSOs that advocate for Lagos’ poor, and the poor themselves, are prone to view investigations by strangers in informal settlements with suspicion. Given a pejorative CSO appraisal of the Nigerian government’s preparedness for disaster response, this study sought to dispassionately study the situation by also interviewing representatives from the NEMA Southwest Regional Office in Lagos and LASEMA. All offered positive views of their agencies’ respective disaster management capacities; as government officials, this bias is expected.

The NEMA representatives were very eager to talk about their education curricula in Nigerian schools and training for three tiers of public volunteers. In addition to the university graduates who owe national service time and professional volunteers, such as civil engineers and medical doctors, they opined that many of their disaster management implementation challenges, namely, a lack of resources, will be addressed by a third tier of grassroots emergency volunteers to number more than 150,000. [41] They were less forthcoming to questions about disaster risk reduction plans, vulnerability and capability analysis and publications in local languages other than English. For each perceived shortcoming, they either cited a lack of funding or shunted responsibility to LASEMA, which are likely legitimate responses except for the lack of local area maps for Local Government Areas or their constituent wards. Based on the survey results, personal interviews with the CSOs most often mentioned as having capacity to assist with disaster management were requested. Although many declined, representatives from eight CSOs agreed to be interviewed in Lagos during June 2014:

- Center for Public Policy Alternatives (think tank)

- Community Development Association

- The Christian Association of Nigeria (interdenominational)

- Organization for Non-formal Education Foundation (Islamic)

- Social and Economic Rights Action Centre

- The CLEEN Foundation (justice sector reform)

- Justice Development Peace Commission (Catholic)

- Arctic Infrastructure (urban development, sustainable design)

Interviewees’ answers to Question 3: What disaster management-related public awareness and education efforts of a government institution are you aware of?

- “Lagos is the only place in Nigeria where no one asks or cares about where a newcomer is from; people come and go all the time. The government cannot properly categorize or count the population, much less control it for [disaster management].”

- “Local government is so corrupt that anyone willing to join or partner with it will be co-opted by oil money. No parishioner in my church wants anything to do with local government.”

- “The government’s arbitrary demolition of slum communities demonstrates the political denial of how many people are affected. For this same reason, you will never get maps of these areas.”

- “If strangers came here with GPS and began community mapping as you suggest, a chief will send his thugs to take the device away and beat the strangers up. The police and chiefs personally benefit from the status quo.”

- “Lagos is a weak state; the proof is that the government channels services via clientelistic networks and not for the broader public good.”

- “Corruption is endemic in local government; this discourages outright compliance with any new regulation, to include even important ones like [disaster management].”

- “Local government gets oil money from the top and for that reason has no incentive to build up from the bottom where [disaster management] is of concern.”The five question interview guide is in the Appendix.

Although anything but sympathetic, several interviewees expressed the importance of understanding particular disaster management challenges local governments face in Lagos. First, Nigerian police are only organized at the federal level. Police officers are frequently rotated in Lagos in an effort to keep them from becoming too cozy with and/or co-opted by local elites. This assignment approach, while perhaps reducing a degree of corruption, hinders development of local knowledge for improving public safety. Moreover, the CSOs stated the local governments suffer from systemic corruption with little to no capacity, resources, political will or incentive to provide basic services. They also stated that Lagos’ recent progress in infrastructure and service delivery has been orchestrated at the state level. Given the pressing day-to-day survival needs for millions of Lagosians, e.g., clean water, sanitation, decent housing and employment, the CSO representatives conceded to some understanding of why disaster management does not rank high on local government agendas.

The author discusses his survey results in Lagos with fellows from the Center for Public Policy Alternatives. (Photo provided by Douglas Batson/Released)

In summary, the interviewees did not (or chose not to) cite a single example of what they agreed should be the easiest disaster management function because of its low cost, i.e., public awareness and education in their respective local government areas. When it was mentioned that NEMA officials gave out their disaster risk reduction brochures and fact sheets, including one on its more than 150,000 grassroots volunteers, the CSO representatives were unanimously dismissive of it as a public relations ploy. None had personally witnessed any emergency drills or seen any NEMA volunteers. The emergent theme from Question 3 was not the efficacy of any one government-led disaster mitigation effort, but a fixation on government indifference to disaster management.

Internal Challenges of CSOs

The concept of Lagosian civil society is often opaque. Thus, the following CSO groups, categorized by Darren Kew, based on eras of their founding in Nigeria, are very useful: 1) the longstanding traditional and religious leaders; 2) trade, student and professional unions established after independence in 1960; and 3) a bevy of rights-and-welfare-advocating NGOs founded since 1999. [42] For Question 4: What can your CSO do to improve disaster management?, the eight interviewees had trouble staying on topic. Their responses drifted into the range and positive impacts of their organizations’ activities, even if these were far removed from disaster management. Still, the interviewees related one overarching theme about the internal challenges Lagosian civil society faces regarding disaster management, its near hopeless fragmentation. The quotes below help explain the rampant pessimism.

- “Authority in the slums is held by traditional leaders with their own brand of patronage politics, informal policing, rules and regulation. External initiation of something new (like [disaster management]) is immediately viewed as subverting the traditional leader’s authority.”

- “Then there is the ‘God factor.’ The believers confuse faith with presumption; they do not believe that disasters will fall upon them; [disaster management], for many, shows a lack of faith.”

- “People mostly affiliate with traditional and religious organizations that in no way engender trust between these groups or foster a common future together.”

- “So many people, men, and women, too, work in the city to sustain families back in their home villages; their roots are not in the city so they are not bound to other people or the locality.”

The interviewees agreed that disaster management education and awareness training may seem like a promising shared goal around which CSOs might coalesce, but it is unlikely to occur prior to a cataclysmic event. To support this view, they cited several reasons all related to a terribly fragmented and clientelistic civil society. First, few Lagosians see themselves as stakeholders in public matters. This includes slum dwellers who view themselves as temporary workers with one foot in the megacity and the other in their rural homeland; those that believe their faith, ethnic or kinship group will care for them in a crisis; or that just focus on eking out a living. Second, even if Lagosians wanted to safeguard their homes against floods, it is unclear to the politically marginalized poor who wields the power and authority to institute disaster management protocols. Third, change requires leadership committed to affecting it. However, Lagos’ poor masses chiefly depend on patronage networks to obtain basic services, so both the formal and informal actors who directly provide or influence service provision (e.g. security, jobs and housing) are more concerned with cementing themselves in positions of power that bestow prestige and profit than working for the public good. Traditional rulers in informal settlements, the very civil society actors needed to champion disaster management, resist altering the status quo.

Local Government and CSOs—Challenges of Working Together for Disaster Management

The challenges in instituting coherent disaster management in the megacity of Lagos might be incrementally overcome by cooperation between local government and CSOs. However, even the high stakes of catastrophic loss in lives and property do not surmount the lack of trust between the two spheres. Because local governments are not autonomous from patronage networks, a lack of legitimacy and social linkages impedes public compliance with imposed rules and regulations. That view first assumes government capacity for disaster management exist s. The 2008 establishment of LASEMA demonstrated political will to improve this service provision. The Lagos State motto is Centre of Excellence, and LASEMA’s human, equipment, regulatory and fiscal resources for disaster management are a marked improvement over the once feral city’s woeful state of preparedness a decade ago. Nevertheless, successful disaster management hinges on positive relationships between government and society. The interview quotes from Question 5: How are CSOs suited for partnering with government to improve disaster management? indicate a very troubled relationship.

“Community Development Associations become irrelevant in a crisis; churches and mosques are secondary. Local chiefs, vigilante groups, market women, etc., are primary to ensure public safety.”

“For [disaster management], we cannot depend on municipal clerks to keep accurate records. Community knowledge must reside within the community. [Disaster management] should be within the domain of civil society.”

“Religious institutions have enjoyed more freedoms from government than other CSOs. Our people view church membership as protection from government. Civic engagement has not been encouraged.”

“Obligations to traditional and religious groups are counterproductive to working with local government.”

“Government first needs to create a framework for CSO participation in [disaster management]. There is currently no platform for dialogue.”

“Vigilante gangs make neighborhoods safe, not the police. The police problematic impede the state-CSO cooperation you are looking for. What should be consistent Rule of Law and security from the State is anything but that.”

“In the event of a catastrophe, first responders would first look to their own families’ welfare and not report to work, or would be unable to get to work due to streets blocked by flood waters.”

The CSO representatives were convinced that the government is wary of working with them because of their prowess as watchdogs against corruption and mismanagement. Some claimed the government views them as agitators, quick to protest, strike and take matters into their own hands, not constructive partners. According to the CLEEN Foundation (a justice sector reform nongovernmental organization) representative, even in rich societies, the public sector alone cannot care for millions of peoples’ welfare when Lagosian traditional rulers’ basic duties include safeguarding and preserving public properties in their domains, protecting the rights of vulnerable populations and

disseminating information. In fact, the representative stated, “CSOs should be government’s most sought after [disaster management] partners because their efforts directly reduce costs to government and bring about the desired social compliance.” He touted CSOs as trusted agents in community record keeping; noting that even poor communities can do a lot to verify and communicate information, integrate local

values into decision-making and combine local knowledge with government data for hazard mapping.

The Social and Economic Rights Action Center (a rights and welfare-based nongovernmental organization) representative declared government news releases and websites that extol disaster risk reduction progress cannot be taken seriously when the government does not even publish neighborhood maps as a first step in assigning its volunteers, or anyone else, areas of disaster management responsibility. Furthermore, the lack of neighborhood maps makes it convenient for the government to deny the severity of the problems caused by slum

proliferation. He was pleased to note that SERAC is partnering with Slum/Shack Dwellers International in order to expand SDI’s 7,000 slum profile maps to Nigeria. [43] He also lauded Map Kibera’s work in Nairobi, Kenya, as an example of desired slum community mapping outcomes. [44]

Figure 2: Traditional Leader Organogram. This depicts the informal power

hierarchy in the Ijora ward of the city. It is fully described in the Appendix. (Released)

This paper has oft cited the role of the poor, but the Lagosian elite also have a critical role to play in bridging the divide between government and CSOs in disaster management.

Concentrations of people, resources and innovative ideas in cities tend to increase living standards. Lagos is no exception and is witnessing the rise of a huge middle class whose interests, along with those of the wealthy elite, are tied to state-led disaster management that leverages the contributions of willing and capable CSO partners. Despite its problems, Lagos has experienced impressive economic growth and livelihood gains to risk it all on continuing a dysfunctional state-CSO dynamic. Lagos truly has become too big to fail.

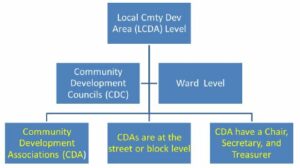

Figure 3: Local Council Development Area/Community Development Association Hierarchies.

Conclusions

The disaster management challenges in Lagos are as numerous as they are severe for both local government and civil society as well as U.S. military and humanitarian forces that would be called to intervene. Understanding and preparing for disasters with strategic forethought will enable the DoD to mitigate long-term risks and prevent the devolution of key societal structures. Challenges in Lagos can be applied to many other global megacities and classifying the major social, governmental and security components of any megacity is a necessity.

In Lagos, the most formidable challenge is overcoming the mistrust that precludes cooperation between the two spheres. Lagos, for all its recent progress, remains a fragile, flood-prone home to 20 million people. Given the high stakes, disaster management offers an auspicious issue to bridge the gulf between local government and CSOs. Of this study’s eight civil society interviewees, three stated the survey questions alone had raised their awareness that partnership with local government in disaster management matters is critical to Lagos’ continued prosperity and peace.

This study suggests to international actors that, as a matter of policy, successful humanitarian relief and disaster response operations in megacities must leverage informal governance and security entities. The data collection of convenience in this study resulted in communication skewed toward Lagos-based NGOs. This study cautions operators, who, likewise, would be tempted to work exclusively with responsive and educated professionals rather than the larger and perhaps corruption-prone, less amenable sectors of Nigerian civil society. While trade unions and religious, ethnic and traditional institutions may lack state-of-the-art office technology and English language proficiency, they stand to be much more effective in mobilizing populations for disaster management-related collective action than recently-minted NGOs. The former’s political muscle and clout with poorer populations are required to institute sound disaster management protocols. For example, at the neighborhood level, informal traditional rulers’ decisions in justice and dispute resolution go nearly unquestioned; rarely is a case referred to the police or courts.

This study significantly adds community development associations to Kew’s three civil society groups. Effective CDAs are essential for improved governance, and by extension, also disaster management, at the neighborhood level. CDAs elect officers who monitor and maintain local government-funded infrastructure projects and prioritize needs to community development councils at the ward level. Based on an interview with a CDA officer, the hierarchical graphic in Figure 3, which parallels the second (local community development area) and third order (ward) administrative divisions of government, was constructed.

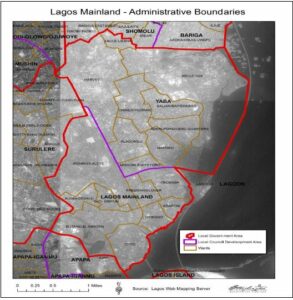

Higher degrees of integration separate global cities from loosely-integrated megacities. Lagos’ vehicle license plates boast Centre of Excellence; the city clearly aspires to move toward the former designation. An increasing number of stakeholders: government, businesses and a kaleidoscopic civil society are aware that Lagos’ recent infrastructure and livelihood improvements require intentional safeguarding. The challenges to disaster management in Lagos are formidable but not insurmountable. Granted, local governments lack resources, but they have not looked to the growing capacities of civil society organizations to engage with even the most basic disaster management tenet of public education and awareness. Disaster management also bodes well to unify a fragmented Lagosian civil society whose informal governance activities help offset the lack of formal bureaucratic norms and municipal services. More local government political will and self-help efforts by disaster-prone populations would demonstrate disaster management as a high priority and facilitate integration of Lagos’ vast polycentric governance systems. A promising starting point for improved cooperation between government and civil society is to enable slum dwellers to map their own communities. As a navigation aid for international actors, this first look study has sorted an imposing Lagosian civil society into four groups and five activity rubrics and includes a comprehensive administrative map of the world’s third largest city. It has narrowed a wide knowledge gap about the utterly Lagosian challenges of megacity disaster management. However, leviathan Lagos is much too large for a single study. Further research is needed on how the level of interaction between government and CSOs in distinct geographic areas leads to either an increase in a population’s vulnerability or resilience in the face of disaster.

Figure 4: Administrative map of Lagos. Source by Washington College Students. (Copyright Digital Globe 2014/Released)

Appendix:

Interview Guide

- Question 1: Your CSO was named as potentially being of assistance in disaster management. What was your reaction to the online questions about CSO roles in disaster response?

- Question 2: Describe a recent disaster in Lagos that resulted in loss of life and/or property.

- Question 3: What disaster management-related public awareness and education efforts of a government institution are you aware of

- Question 4: What can your CSO do to improve disaster management?

- Question 5: How are CSOs suited for partnering with the government to improve disaster management?

More on Figure 2: Traditional Leader Organogram

The Oba is referred to as His Royal Majesty, Ojora of Ijora and Iganmuland. He is the hereditary monarch with all the trappings of traditional authority, and his ruling house appoints him to occupy the throne. The Baales, Baloguns and the Iyalodes are the traditional agents appointed by the Ojora (Oba). They may not hold hereditary or lineage positions rather, they hold their positions only at the discretion of the Oba. They are accountable to the Oba for the exercise of their powers, including dispute resolutions in the community. Some of these traditional rulers’ basic duties are to:

- Promote peace and stability in their domain

- Mediate and settle disputes, domestic and others

- Preserve customs and cultural values

- Safeguard and preserve public properties in their domain

- Disseminate information and sensitize the public

- Protect the rights of the vulnerable in the society

- Provide necessary information on matters relating to their jurisdiction

- Advise the government on customs, traditional matters and security issues

Lagos was made of 20 Local Government Areas. In 2007, the Lagos State Government subdivided the LGAs to create 37 additional second-order administrative divisions. However, the new second-order divisions are referred to not as LGAs, but as Local Council Development Areas. Because of state/federal political wrangling, the Local Community Development Areas do not appear on official Nigerian maps. For the past eight years, confusion abounds because the original 20 Local Government Areas place names, formerly covering all of Lagos State, could refer either to the original LGA or now the truncated geographic extent.

Via a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between Washington College (Chestertown, Md.) and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the college’s geographic information systems students produced a digital map from data provided by the Lagos State Independent Electoral Commission. This map image displays a portion of the de facto administrative structure, namely, Local Government Areas/Local Council Development Areas and their constituent ward boundaries. For example, Yaba Local Council Development Area was carved from the Lagos Mainland Local Government Area.

REFERENCES

[1] Kilcullen, D. (2012). The City as a System: Future Conflict and Urban Resilience. The Fletcher Forum, 36(2), 19-39.

[2] Obono, O. (2007). A Lagos Thing: Rules and Realities in the Nigerian Megacity. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 8(2), 32.

[3] The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Society defines Disaster Management as “the organization and management of resources and responsibilities for dealing with all humanitarian aspects of emergencies.”

[4] Stanislawski, B. (2010). Mapping Global Insecurity. The National Strategy Forum Review, 19(4).

[5] Penner, G. (2014, July 9). A Framework for NGO-Military Collaboration. Small Wars Journal.

[6] David, A. (2013). Civil Society Engagement in the Sulu Archipelago: Mobilizing Vibrant Networks to Win the Peace. (Thesis presented to the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.)

[7] Demographia (2013). World Urban Areas, 9th Edition, Table 1.

[8] Huriot, J. & Bourdeau-Lepage, L. (2006). Megacities vs. Global Cities: Development and Institutions. European Regional Science Association. Conference Paper.

[9]Oseni, A. (2013, May 21). Megacity Projects Leave Slum Dwellers with Uncertain Future. The Premium Times.

[10] Simon, R., Adegoke, A. & Adewale, B. (2013, March). Slum Settlements Regeneration in Lagos Mega-city: an Overview of a Waterfront Makoko Community. International Journal of Education and Research, 1(3) 2.

[11] Mackay, M., Webster, G.& Kermeliotis, T. (2012, June 15). Lagos: Engulfed by Floods. Cable News Network International.

[12] Koolhaas, R., Boeri, S., Kwinter, S., Tazi, N. & Obrist, H. (2001). Mutations, Barcelona, Spain: Actar Press.

[13] Butsch, C., Etzold, B. & Sakdapolrak, P. (2009, June 16). The Megacity Resilience Framework. United Nations University Institute for the Environment and Human Security. Bonn, Germany.

[14] Kalan, J. (2014, May 8). 10 Million Sardines in a Sea of Skyscrapers: How Sprawling Megacities – from Lagos to Mumbai – Might Just Save the World. Foreign Policy.

[15] Kourtit K. & Nijkamp, P. (2013, June). In Praise of Megacities in a Global World. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 5(2).

[16]Glaeser, E. (2011). The Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Healthier, and Happier, Pengiun Press, p. 270.

[17] Khanna, P. (2013, March 26). Cities Not Countries Will Once Again be Key to World Order. The National.

[18] Barber, B. (2013). If Mayors Ruled the World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities, Yale University Press.

[19] Davis, M. (2006). Planet of Slums, Verso Books, pp. 23, 201.

[20] Castells, M. (1998). Why the Megacities Focus? Megacities in the New World Order. The Megacities Project Publication, p. 2.

[21] Pieterse, E. (2008). City Futures: Confronting the Crisis of Urban Development, Zed Books.

[22] Setchell, C. (1995). The Growing Environmental Crisis in the World’s Megacities. Third World Planning Review, 17(1).

[23] Haynes, J. (1995). Popular Religion and Politics in sub-Sahara Africa. Third World Quarterly, 16(1) p. 89.

[24] Meidinger, E. (2002). Law Making by Global Civil Society: The Forest Certification Prototype. Social Science Research Network, 22.

[25] Obono, O. (2007). p. 31.

[26] Landau, L. (2013, April 18). Recognition, Solidarity, and the Power of Mobility in Africa’s Urban Estuaries. Social Science Research Network.

[27] Defense News, (2014, Aug. 30). U.S. Army Sees ‘Megacities’ as Future Battleground.

[28] Chief of Staff of the Army, Strategic Studies Group. (2014). Megacities and the United States Army: Preparing for a Complex and Uncertain Future.

[29] A term introduced by Edgar Pieterse in City Futures: Confronting the Crisis of Urban Development, p. 3, urging caution before one pronounces on what is going on in a city based solely on positivist measures.

[30] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, (2001 Revision). World Urbanization Prospects. p. 91.

[31] A term coined by Robert Muggah in Megacity Rising. International Relations and Security Network, Zurich, Switzerland, October 24, 2013.

[32] Kraas, F., Aggarwal, S., Coy, M., Heiken, G., de Mulder, E., Marker, B., Nenonen, K. & Yu, W. (2005). Megacities: Our Global Urban Future. Earth Sciences for Society Foundation, Leiden, the Netherlands.

[33] du Gramont, D. (2014). Constructing the Megacity: The Dynamics of State-building in Lagos, Nigeria, 1999-2013. (Master’s Thesis; Department of Politics and International Relations, Oxford University, U.K.) p. 2.

[34] Eko Atlantic City (2015).

[35] Ibezim-Ohaeri, V. (2013, Nov. 8). Eko Atlantic City Project Will Further Widen the Gap Between Rich and Poor. Spaces for Change (S4C).

[36] Lagos State Emergency Management Agency (LASEMA) 2014.

[37] Haruna, G. (2013, Aug. 28). Nigeria: Working Against Flood Disaster.

[38] Sidiq, A. (2012). A Look at Nigeria’s Bourgeoning Emergency Management System: Challenges, Opportunities, and Recommendations for Improvement. U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

[39] Adapted from Titilope Mamattah, Building Civil Society in West Africa: Notes from the Field. The Handbook of Civil Society in Africa, Ebenezer Obadare (Ed.), Springer, 2014, p. 155.

[40] Corroborated after the June 2014 interview in the Daily Independent, NEMA Will Recruit 154,000 Grassroots Volunteers in Nigeria.

[41] Kew, D. (2005, May 13). The Role of Civil Society Groups in Strengthening Governance and Capacity: Avenues for Support. Unpublished paper briefed at the Conference on Aid, Governance and Development, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

[42] In 2014 The Santa Fe Institute partnered with Slum/Shack Dwellers International to visualize SDI’s 7000 slum community profiles; the first are in India and Uganda.

[43] The Map Kibera (2014).

About the author:

Douglas Batson joined the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) as human geographer in 2004. He holds a Master of Education from Boston University and a Bachelor of Science in geography from Excelsior College. Batson is a member of the Association of American Geographers and was the recipient of its 2014 M. F. Burrill Award. He recently completed a National Intelligence University research fellowship on megacity disaster response. He previously worked for the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Department of Justice and is retired from the U.S. Army Reserve.