Traffic police at work before De-Baathification. Baghdad, June 2003. (Courtesy of Holly Hughson/Released)

Calling itself the Islamic State may one day be known as the greatest propaganda coup the Islamic State in Iraq and Levant achieved. [1] It triggered a legion of debate by media pundits, reinvigorated the Islamophobia industry and transitioned individuals fearful of difference into hardened killers around the world. Misunderstanding ISIL’s relationship to religion misdirects the efforts being used to defeat it.

In the name of religion, ISIL exploits three factors in the furtherance of their goal: local power vacuums in Iraq and Syria, regional disillusionment with power surplus in the Middle East and conceptual alienation from power in Western countries. Whether a jihadist deferential to al-Qaeda, Western country deferential to sectarian regimes in Syria and Iraq or families and friends deferential to non-Muslim cultures, ISIL appears strong where others appear weak.

To defeat ISIL and further the cause of stability in the Middle East, the United States must understand ISIL’s ideology functions across different lines of identity. Defeating or even degrading the geographical control of ISIL is not sufficient; as long as they have local support, ISIL can hold or retake ground. A viable strategy for victory asks the United States to orient to certain uncomfortable, yet powerful and well-understood dynamics in play that are not easily reversed: Sunni opposition to the systemic abuses of the Shia dominated Iraqi and Syrian regimes and the absence of credible, representative authority generally in the Middle East.

Maj. Gen. Michael Nagata, commander of Special Operations Command Central forces in the Middle East, who is leading the U.S. fight against ISIL, has expressed his frustration in trying to understand the appeal of the complex enemy presented by ISIL. In 2014, he assembled a non-traditional group of experts [2] through the Pentagon, State Department and intelligence agencies. These experts were charged with examining this complex, dynamic terrorist organization by looking at religious influences, psychological tactics, marketing manipulation and economic resource control. Whatever insights the group provides, there must be high-level political will to back the military campaign while

simultaneously navigating dynamics from which ISIL gains strength.

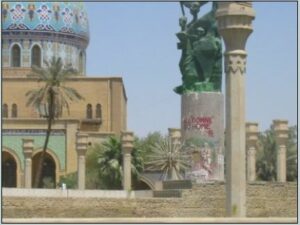

Saddam Hussein is missing. Baghdad, June 2003. (Courtesy of Holly Hughson/Released)

Authority issues

Mounting evidence shows support for ISIL has as much to do with issues of authority itself and as it does with personal belief in the authority of religion. One analogy to explain ISIL’s success is the mafia. Members of the mafia are not necessarily anarchists who reject the principle of state authority to govern, regulate, tax and protect its citizens. Rather, individuals join or find it hard to resist a mafia organization because they feel under-represented and vulnerable, outside of the protection of the formal state’s authority. Therefore, a parallel system of governance, staffed by a bureaucracy with leadership, junior enforcers, tax collectors and soldiers, arises.

French journalist and former ISIL hostage, Didier Francois, told CNN he knew he was held by ISIL because they openly claimed they were the Islamic State. [3] He clarified, “It was not a religious discussion. It was a political discussion.” Francois describes a politically shrewd ISIL leader in al-Baghdadi, whose strategy is honed from a sectarian legacy sharpened by the past 12 years since losing the protection of Saddam Hussein’s government. “He always tries to push the Sunni tribes, the Bedouins to fight against the Shia, or the Yazidi or the Christians. He always tried to play communities, one against the other. That is how he survives. That is how he recruits.” Acknowledging the foreign fighters recruited, Francois explains that by far “the strongest part of his organization are the tribes, the local Sunni tribes who are actually following him for political reasons.”

Only one journalist has been allowed to travel into ISIL controlled territory and safely return home. In 2014, Juergen Todenhoefer spent six days in Mosul, where he interviewed and filmed ISIL fighters. On return, he said, “I thought I would find a brutal terrorist group and I met a brutal country.” Most disturbing for him was to hear their enthusiasm for killing their enemies, which he listed as anyone who does not follow their interpretation of pure Islam. In an interview, Todenhoefer confirmed what is broadly understood, ISIL’s enemies include Shia, Christians, Yazidis, Hindus and atheists. [4] He offered an additional insight, “They (ISIL) even want to kill all the Muslims in the Arab countries and in the Western world which are democratic. Because to be democratic means for them, that is somebody puts the laws of human beings above the law of God.” For ISIL, there is no separation of religion and the state, but there is absolutely a separation of their religious state and any alternative political ideology.

These rare eyewitnesses who lived to relate their experiences with ISIL counter the argument that ISIL derives its success and power to recruit because it is Islamic. Its primary appeal and success, distinguishing it from fellow jihadists, is that it aspires to be a state that is Islamic. The threat to Iraq, the Middle East and global security is the existence of the state, not the religion. The United States and its allies must defeat the state ISIL has become.

What ISIL believes is not important for the fight against them. Whether they believe they are Islamic and this belief translates into a dress code for women, personal hygiene requirements for men or using children as executioners makes no difference when fighting them. The question is: Why does their ideology work at all? CNN contributor Fareed Zakaria recently posed this question in an opinion column entitled, “The limits of the ‘Islamic’ label.” [5] He quoted Barnard College professor Sheri Berman, “An ideology succeeds when it replaces some other set of ideas that have failed.” Taking this as a working thesis, the question becomes: What are the failed ideas that ISIL is able to exploit? By looking at ISIL’s record of relative success in recruiting fighters as well as civilians and exporting a brand beyond the Middle East, a distinct pattern of a mafia-esque counter-narrative emerges.

At once, there is an adolescent boldness twinned with moral outrage at a record of abuse and alienation along lines of identity. Even ISIL’s enemies acknowledge it succeeds in the wake of gross abuse of power and ethno-sectarian violence to which all parties have committed. The extraordinarily fine line ISIL’s ideology exploits is one of an illegitimate, yet justifiable, challenge to authority.

Graffiti in Freedom Square. Baghdad, June 2003. (Courtesy of Holly Hughson/Released)

Defiance

ISIL evolved from the Islamic State in Iraq, formed in 2006 by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi as al-Qaeda’s presence in Iraq. When al-Zarqai’s successor, Umar al-Baghdadi, was killed in a military strike in April 2010, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi succeeded him. The group was fairly quiet for the next couple years and part of the opposition groups fighting the Syrian government. The death of Osama bin Laden in 2012 was the death of charismatic leadership for al-Qaeda once Ayman al-Zawahiri was in charge. This leadership void provided a strategic opportunity for al-Baghdadi.

In a recent report for the Brookings Institute, Princeton scholar and ISIL expert, Cole Bunzel, traced the group’s ideological journey as their self-declared caliphate emerged from direct confrontation and challenge of al-Qaeda’s leadership. [6] On April 9, 2013, al-Baghdadi released an audio statement announcing that Islamic State in Iraq was expanding to Sham, the Arabic word for greater Syria. It was now Islamic State of Iraq and Sham. In his message, al-Baghdadi took the liberty to absorb the al-Qaeda affiliate fighting in Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra, declaring it subordinate. Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani, Jabhat al-Nusra’s leader, immediately rejected the announcement and reaffirmed his loyalty to al-Zawahiri. However, none of this mattered to ISI, which moved into Syria and begin drawing al-Nusra’s fighters to its ranks.

Several months into this fratricidal dispute, al-Zawahiri intervened and ruled that ISI and al-Nursra should remain separate. In his letter leaked to Al Jazeera, al-Zawahiri reveals the al-Qaeda leadership did not anticipate the scale of al-Baghdadi’s aspirations by admitting they had “neither been asked for authorization or advice, nor have we been notified of what had occurred between both sides.” [7] Like an aging father trying to separate his sons from fighting, he lays out explicit faults on both sides and confers approval for the two groups’ leadership and area of responsibility.

Al-Baghdadi simply rejected the order, indicating al-Zawahiri was no longer in charge. [8] Without al-Qaeda’s authority or influence, ISIL entered a new era with seemingly no outer limits. Their flagrant defiance of authority sent a powerful signal to the global jihadist community. Combined with an unprecedented media campaign in terms of professional quality and psychological manipulation, the core of ISIL’s ideological appeal comes from its claim to stand up to weak leadership.

In parallel with ISIL’s dispute of al-Qaeda’s authority, the person of al-Baghdadi himself makes a more subtle yet distinct challenge to the religious establishment. Through his biographer, al-Baghdadi is styled as an outsider authority. Amongst the requirements for validating a claim to caliph, the biographer delineates al-Baghdadi’s lineage to the Prophet Mohammed as well as his basis for religious authority to interpret the Quran. [9] Instead of receiving his theological training at the bastion of Sunni religious authority, al-Azhar University in Cairo or the Islamic University of Medina in Saudi Arabia, al-Baghdadi received his Ph.D. from the Islamic University of Baghdad.

Al-Baghdadi presents a more modest Sunni pathway to caliph, evoking the humble origins of the Prophet Mohammed. He claims a far more traditional, religious education on Islamic culture, history, sharia and jurisprudence, than either of al-Qaeda’s leaders: Bin Laden was trained as an engineer and al-Zawahiri as a medical doctor. Virtues of religious purity and humility are paired with defiance of theological and political establishment and serve as symbolic and literal rejection of both failed and despotic power, even as they replace it with their own authoritarian regime.

In one fell swoop of declaring a caliphate with al-Baghdadi as caliph, ISIL usurped both the Sunni and al-Qaeda established elite. It is the perfect formula to appeal to a disaffected, politically unrepresented demographic worldwide. Even more powerful, their righteous indignation at the failure of unchecked abuses by regional regimes is broadly shared by millions, if not their choice for violence.

Spiral descent over Baghdad, June 2003. (Courtesy of Holly Hughson/Released)

Authority crisis

The symbolism of al-Baghdadi as a rogue caliph who does not need the approval of the Sunni religious or political elite is central to the appeal of ISIL itself. Its upstart ability to challenge established religious and ideological authorities is symptomatic of a much broader breakdown of religious authority within Islam. H. A. Hellyer explains this crisis of authority in an essay responding to the high profile debate over whether ISIL was Islamic. [10] While there is no hierarchical ecclesiastical structure within Sunni Islam, interpretation of texts to establish legitimacy, has traditionally required the ability to demonstrate a historical pedigree. Individual interpretation was unthinkable as a basis for argument. Rather, when a scholar puts forth an interpretation, he includes the “master x” with whom he studied, who was himself a student of “master y,” who had the privilege of studying with “master z, whom all acknowledge” and so it continues back to the Prophet himself. The stronger this “chain” or sanad, the greater the chance of the interpretation gaining broad support. Hellyer explains, “These systems do not simply establish the transmission of texts between successive generations, but also the understanding of those texts.”

Islam joins its forerunners of Christianity and Judaism in being a “religion of the book.” All three religions have a history of engagement with sacred texts in a dynamic relationship of interpretation by established authorities, reformers and revolutionaries alike. As a result, systems of authority have emerged over time. It is precisely these systems of authority that radical Islamic groups rejected in favor of their own interpretation of both Islam and the state. ISIL’s declaration of a caliphate with al-Baghdadi as caliph did not have any of the checks and balances of dialogue with Islamic theological and legal tradition. The result is an antiestablishment authoritarian upstart that has fostered a raw, unbridled jihad.

ISIL’s oxygen

The Syrian government’s prosecution of war against its own citizens has inadvertently mobilized tens of thousands of foreign fighters for its opposition, which in turn has empowered ISIL. Through its social media presence, ISIL has successfully portrayed itself as the “most pure” of the jihadist opposition and most capable of standing up to the Assad regime.

The unchecked record of Syrian civil war is a daily reminder and signal of the impotence of foreign powers to enforce even their own United Nations Security Council Resolutions. [11] The perceived lack of action, despite the humanitarian crisis, has been a significant and powerful recruitment force for both jihadists and opposition forces alike. As long as the Syrian regime can perpetuate its brutal, indiscriminate attacks on its own civilian non-combatants with impunity, ISIL will continue to co-opt foreign and domestic recruitment for jihad and make its case as the protector of targeted, marginalized Sunnis worldwide.

In parallel to its role in Syria, ISIL’s growth, geographic and political success in Iraq cannot be separated from the years of abusive sectarian rule by the Shiite-dominated Iraqi government since it assumed power in 2004. The brief respite from this rule, when Sunnis chose to support the American military surge over the radical jihad of al-Qaeda in Iraq, was a risk that did not ultimately pay off. Sunni communities were met with continued marginalization and betrayal from their government. Even the former leader of the Sons of Iraq admits a second awakening cannot now be replicated because of how systematic alienation has been incorporated into the legal framework. [12] Iraq’s counterterrorism laws can be interpreted so that, “any Sunni can be arrested and accused of terrorism without cause, convicted without due process and pass years in jail without a trial.”

Satellite dish in Iraq. (Courtesy of Holly Hughson/Released)

Cleaning karez in Kirkuk. (Courtesy of Holly Hughson/Released)

Powerful dynamics complicate effective, decisive action in the fight against ISIL, starting with the escalation of direct conflict between both state and non-state regional powers. The lack of will at the UNSC to enforce its own resolutions regarding Syria and the broader design flaw whereby Cold War rivals block action by veto, render the mechanism broken. Nuclear negotiations with Iran have complicated the formation of the coalition fighting ISIL, which only serves to affirm their appeal. Gross human rights violations are committed by all sides of the political, ethnic sectarian divides and it is difficult to imagine who will be first to put down their weapons in the name of diplomatic resolution. As long as Syrian and Iraqi Sunnis have no viable alternative, and the present Shia-dominated Syrian and Iraqi governments operate with impunity, ISIL’s ideology has oxygen to remain alive.

Revisiting responsibility and renewal

Maj. Gen. Nagata’s task is re-setting a compound fracture amongst mortal enemies whose fissures are deepened every single day as Middle Eastern regimes, ISIL and its jihadist ilk, and sectarian militias prosecute their campaigns of terror. While he has been honest about the bewildering, complex challenge ahead, has the nation had the courage to define the fight against ISIL?

Given the operational environment of a sustained, catastrophic humanitarian crisis overlapped with unstable states unwilling or unable to govern and protect all of their citizens, the United States risks defining the mission either too narrowly or too broadly. The narrow mission is to defeat ISIL as a landowning entity, foreign fighter jihadist recruitment base, and immediate threat to the governments of Iraq and Syria. The complex challenge of the fight is understanding and countering the ideological framework which ISIL has so effectively captured. The key to their appeal is found in what unites their broad demographic of support that defies categorization apart from a consistent pattern of alienation from and willingness to challenge established authority.

ISIL’s ideology does not eliminate challenges from within its organization. Tensions are increasingly reported between foreign and domestic fighters and their relative privileges. [13] Nor is ISIL’s ideology immune to the challenge of hierarchy inherent within Islam or what has been termed, second-class jihad. [14] They must deal with the pressure of battlefield reversals as Kurdish and Iraqi forces have regained territory and the tedious responsibility of managing and providing for a population facing shortages of gas for cooking or medical supplies. [15]

Regardless of these vulnerabilities, the West should not be lulled into viewing ISIL’s relative setbacks as a triumph. ISIL is only one manifestation of a crisis of religious and political authority in which nations worldwide are participating to a varying degree. First, the protracted, civil wars and failed or floundering states of Syria, Iraq, Libya and Yemen present the most obvious case for crisis. Second, the failure of the Arab Spring to gain traction through peaceful demonstration and the demand for representation has the majority populations simmering under reinforced authoritarian control. Third, Western nations who espouse democracy and representative government have failed to support the courageous masses who stood up for their right to be represented. Instead of open support of this democratic call and echo of our own political origins, Western governments have appeared hypocritical about their own values in choosing instead the preservation of strategically powerful alliances and abiding by a broken UNSC whose resolutions appear to be the token gestures of the entitled.

Clean-up campaign in Kirkuk. August, 2003. (Courtesy of Holly Hughson/Released)

Caught in a Cold War paradigm

Traditionally, when a national security challenge arises in the Middle East, the United States has a single point of contact. Substantive dialogue could occur through a single phone call to the strongman in charge who, with an investment in his military or economy, allowed the United States to manage by proxy, the actions supportive of its national interests. In return, the United States turned a blind eye to tactics of population control. The United States is paying a price for this relationship in terms of the populations’ perceptions of our duality: Preach democracy and freedom until a security concern or economic interest supersedes our proclaimed values.

The conventional, asymmetric, insurgent wars being fought in the Middle East are along multiple lines of identities and are easily overwhelming. However, as any shrewd practitioner of strategy would say, crisis begets great opportunity.

Time to take responsibility

In terms of governance in Iraq and Syria, the West must revisit mistakes made over the past decade. The immediate vacuum ISIL and regional powers exploit today was created in 2003 with the invasion of Iraq, but the vacuum is also a product of a much longer historical record in Iraq and the region. As part of the international community and signatories to the Geneva Conventions and International Humanitarian Law, the United States has an opportunity to support a framework that protects civilian noncombatants and provides a mechanism to disarm and demobilize those on all sides of sectarian and ethnic division in Iraq and Syria.

In the fight against ISIL and the instability in the Middle East, the United States has a unique opportunity, which is twofold. First, it may send a powerful signal to its allies and to the overwhelming majority of the population in the Middle East, that it affirms the commitment to democratic values and representative governance. In order to do this credibly, the United States must acknowledge a record to the contrary, of supporting non-democratic regimes which the Arab Spring attempted to unseat. Next, the United States may address its own domestic divisions through bipartisan acknowledgement that both parties made critical mistakes and costly errors in judgment in Iraq and the region. Showing it has the maturity and capacity as legislators and elected officials to accept lessons learned would be a politically savvy move and opportunity to show bi-partisan humility.

Thinking of ISIL as the militarized arm of the Arab Spring provides a very productive angle on defeating it and a unique perspective of the fuel that has ignited each of the present conflicts in the Middle East. In order to counter the appeal of ISIL’s outsider ideology, the United States bears responsibility for its leading role in the breakdown of authority in the region.

Only through empathy and the honest cultural self-examination that such a strategy demands can questions be identified and asked and find the unity (and subsequent loss of paralysis) to defeat the common enemy that is ISIL. Without this process, its ideology will metastasize, with franchise jihad adopted by the marginalized, alienated individuals everywhere. Any ideology that forcefully draws lines and division amongst society, whether it comes from the state or the backyard, is a malignancy that cannot be ignored. The United States must keep unity as the goal of diversity, promote acceptance within a framework of human rights, and check instinctive perceptions in order to build bridges across even the greatest differences.

Defeating ISIL will continue to be a military fight for some time to come. Defeating ISIL’s political ideology must result in credible, representative governance in the Middle East. This will not be an easy path as U.S. history, including civil war, reminds us. The traditional relationships between the United States and regional power brokers must be re-examined. Attempts to preserve or restore the former status quo are naïve, hypocritical, and will sustain the ideology of ISIL.

Boys outside an ice cream shop in Erbil. August, 2003. (Courtesy of Holly Hughson/Released)

There are no easy answers to how stable, representative government will occur in Iraq, Syria and the region. Enforced buffer zones to simply halt the atrocities and establish humanitarian access will be politically fraught with complicated risks yet may be unavoidable. A critical step on the pathway to peace may be found in a truth and reconciliation process. This process would involve representation from Sunni, Shia, Kurdish and other minorities with the twinned goals of each community owning its actions that were divisive and to stimulate equitable, representative distribution of resources. The greatest challenges hold the greatest opportunities. In the end, all sides have an interest in viable governance. The Arab Spring was a reminder that the Cold War is over; it is time for a new paradigm.

Admitting weakness or vulnerability is not easy. Not as an individual, not as a nation. But only in an honest assessment of limitations, can the United States clearly see its strengths and thus identify a credible pathway forward for national security.

About the Author

Holly Hughson is a humanitarian aid worker and civil-military trainer with an extensive background in rapid assessment, program design, management and monitoring of operations in both humanitarian emergencies and post-conflict settings. Her experience includes work in Kosovo, Sudan, Iraq, Russian Federation and Afghanistan. Presently she is writing a personal history of war from the perspective of a Western female living and working in Muslim countries. She works as an instructor and advisor on humanitarian aid and early recovery to joint, coalition and inter-agency training exercises at multiple U.S. bases in the United States and Europe.

References

[1] The organization known as ISIL, ISIS and Daesh are all names which evolved from the earlier al-Qaeda affiliate “Islamic State of Iraq”. For the sake of continuity with Department of Defense preference, ISIL is used in this article.

[2] Meet General Nagata, the Man Leading the Mission to Defeat ISIS. (n.d.) NBC News.

[3] Krever, M. (2015, February 4). ISIS cared little about religion, says Francois. CNN.

[4] Hawley, C., & Longman, J. (2014 December 23). Rare Islamic State visit reveals ‘brutal and strong’ force. BBC News.

[5] Zakaria, F. (2015, February 19). The limits of the ‘Islamic’ label. The Washington Post.

[6] Bunzel, C. (2015, March). From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State [PDF file] (Analysis Paper, The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World).

[7] Al-Zawahiri, A. Translation of Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Letter. [PDF file].

[8] Iraqi al-Qaeda chief rejects Zawahiri orders. (2013, June 15). Al Jazeera.

[9] Zelin, A. (2014, July 31). Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi: Islamic State’s driving force. BBC News.

[10] Hellyer, H. A. (2015, February 20). This stupidity needs to end: Why the Atlantic & NY Post are clueless about Islam. Salon.

[11] Hartberg, M., Bowen, D., & Gorevan, D. Failing Syria: Assessing the impact of UN Security Council resolutions in protecting and assisting civilians in Syria.

[12] Ghaffoori, S. (2014, September 22). How to get Sunnis to turn against ISIS. New York Daily News.

[13] Sly, L. (2015, March 8). Islamic State appears to be fraying from within. The Washington Post.

[14] Hughson, H. (2015, January 23). Unmasking the Executioner: What This Gesture Means and How It Can Help in the Fight Against ISIS. Small Wars Journal.

[15] Mosul diaries: Poisoned by water. (2014, December 19). BBC.